Edogawa Craft Stories

Edo Glass: Blowing Tradition into the Future through Handcrafted Glasswork

Edo Glass

Tajima Glass Co., Ltd.

Tajima Daisuke

Tajima Glass Co., Ltd., located in Matsue, Edogawa City, has been crafting glass since its founding in 1956. Third-generation president Tajima Daisuke works alongside a team of around 50 artisans, honoring the time-honored techniques of Edo glass—a tradition that dates back to the Edo period—while also pursuing innovative products tailored to modern lifestyles.

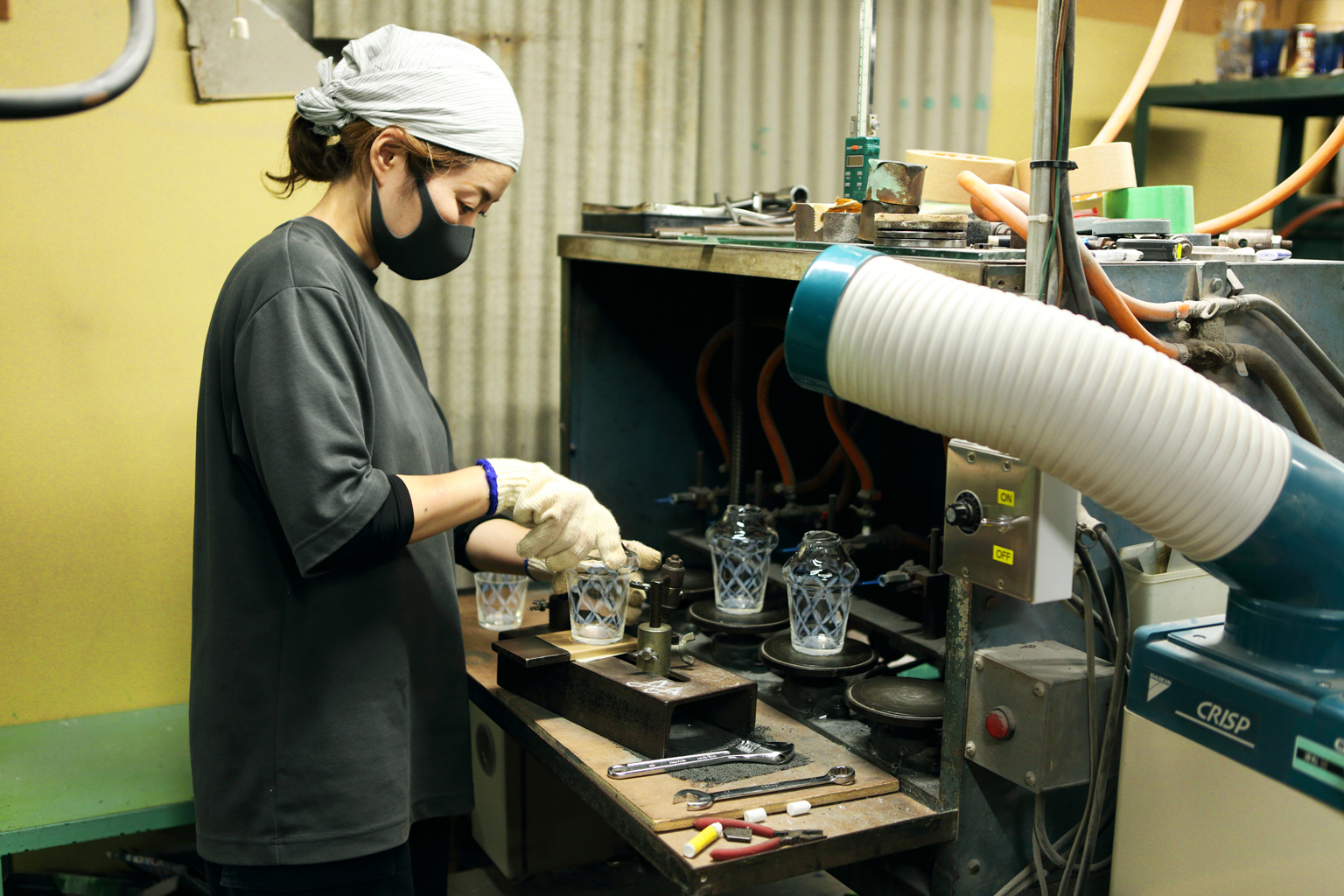

Step inside the factory and you’re immediately hit by a wave of heat. At the center of the workshop stands a massive melting furnace, where glass is liquefied. Around it, dozens of artisans of all ages and genders work up a sweat as they go about their craft.

Our visit took place in mid-June. “To keep the glass molten, we have to maintain temperatures between 1,300 and 1,500 degrees Celsius. It gets incredibly hot in summer,” says company president Tajima Daisuke as he shows us around the workshop, wiping his brow with a towel slung around his neck.

The dome-shaped furnace in the background contains crucibles embedded inside. It’s within these that the glass is melted.

The Subtle Beauty of Handmade Glass, Born from Teamwork

Edo glass refers to glassware made using traditional methods handed down since the Edo period. Techniques include katafuki (mold blowing), where molten glass is inflated within a mold, and nobashi, where tools are used to pull and shape the glass. At Tajima Glass, these techniques are used to craft a wide range of products, from drinkware to guinomi (sake cups).

To make patterned glasses, heat from a torch is applied to the blown glass to separate the body from the stem. It’s a delicate operation—get it wrong and the whole piece can shatter.

Handmade often means small-batch, but not at Tajima Glass. One of the company’s standout features is its ability to scale production without sacrificing the quality of handcrafted work. The secret lies in a well-established system of division of labor, built around teams of skilled specialists.

“Even within the term ‘glass artisan,’ there are many areas of expertise,” Tajima explains. “One may excel at shaping wineglass stems. Another might be great with large vases. Another is a master of layered glass. We form 4–5 person teams centered around each of these strengths for production.”

Tajima Glass’s popular Mt. Fuji Glass being made. The faint orange glow of the glass shows just how hot it is.

This team-based process makes it possible to maintain the tactile, unique quality of handcrafting while still producing efficiently at scale. Depending on the item, the factory can turn out roughly 2,000 to 2,500 pieces of Edo glassware per day.

Human Touch and Technique Brings Expression Machines Can't Replicate

“The character of a piece—its expression—can never be recreated by a machine,” says Tajima. One of the key techniques, katafuki (mold blowing), involves gathering small amounts of molten glass on a blowpipe and inflating it within a mold. But even using molds, the process is far from mechanical.

“For example, if you’re aiming for a thickness of 1.5 mm, our artisans know from experience exactly how much glass to gather, and how to control their breath to get just the right thickness. To smooth the surface, they rotate the blowpipe while inflating the glass, either in one direction or alternating, depending on the piece. It’s all adjusted by feel.”

Katabuki-blown glass requires especially uniform breath control so the design doesn’t warp, a process only seasoned artisans are entrusted with.

On the day of our visit, the team was making parfait glasses. One artisan blew the bowl of the glass, while another shaped the stem, joining the two in perfect synchronicity. The molten glass cools rapidly once out of the crucible, so all of this has to happen in seconds. Watching it unfold is mesmerizing.

With flawless timing, glass softened to just the right degree is passed over and shaped into a base in a matter of moments.

“There’s a certain drive among craftspeople, the feeling that ‘I’ll conquer anything with my own skill.’ That spirit pushes them to hone their strengths even further. Which is why I believe my role, as president, is to truly understand market needs and develop products that allow our artisans’ techniques to shine.”

Hit Products Born from a Global Perspective

Tajima Glass centers its product development around the question: “What makes Edo glass truly valuable?” We asked Tajima how he comes up with ideas.

“If you’re simply making something by hand that could be mass-produced by machine, just to charge more, customers won’t be convinced. The first thing I ask is, ‘Does this make people think handmade is fun? Is it something special in both design and texture?’ That’s the baseline.”

A prime example of innovation rooted in tradition is the company’s signature Mt. Fuji Glass series, currently available in three designs. The first, the Mt. Fuji Hoei Glass, debuted in 2011. Pour beer into the trapezoid-shaped glass and Mount Fuji appears in the foam, complete with snowy peak.

The indentation on the side represents the Hoei Crater, formed by a mid-Edo period eruption. It's designed for easy grip as well.

The second design, released in 2013, is the Mt. Fuji Sake Glass, which reveals the iconic mountain shape when flipped upside down. It uses the traditional technique of kise-garasu—a layering of colored glass over clear.

The snowy summit is depicted using a sandblasting technique. The cup won the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Award at the 54th Nippon Omiyage Awards .

The third and final design in the trilogy is simply called the Mt. Fuji Glass, released in 2015. Its design features a Mount Fuji-shaped impression in the base of a rocks glass, with the liquid reflecting color onto the “mountainside.”

The originality of the design struck a chord—over 900,000 units have sold since its release.

“With the rise of inbound tourism, we wanted to create something that would resonate not just in Japan but with people from around the world. We asked ourselves, ‘What’s a design that clearly feels Japanese, even without explanation?’ We were lucky: people started sharing videos of pouring drinks into the glass on social media, which really helped spread the word.”

Now the company is focusing on a new project: promoting a line of black Edo kiriko cut glass made from a unique jet-black glass developed by Tajima’s father, the former company president.

Tajima Glass has been producing kise-garasu, the base material for Edo kiriko, for over 40 years. In response to a shrinking number of artisans, they began training their own kiriko craftsmen 13 years ago. The black Edo kiriko represents a fusion of two traditional techniques—Edo glass and Edo kiriko—and stands as a symbol of the company’s future-facing philosophy.

Kise-garasu involves fusing a thin layer (just 0.3mm) of colored glass onto clear glass. Achieving a true jet-black finish is extremely difficult.

Building Ties with the Community with an Eye on the Next 30 Years

Tajima Glass has called Edogawa City home for nearly 70 years—and for Tajima Daisuke, it’s also filled with childhood memories.

“I grew up in Urayasu in Chiba with my parents, but my grandfather—the founder—lived here at the factory. This area has changed a lot. It’s a residential neighborhood now, but back then it was mostly farmland.”

“Glassworkers start early, so my dad would drive us over and we’d arrive by 6 a.m. I’d eat breakfast with my grandmother, then my grandfather would walk me to preschool,” recalls Tajima.

That shared family history is deeply tied to the company’s identity and to its relationship with the community. Today, Tajima Glass actively opens its doors to the public.

“We host school visits for local elementary students, and during neighborhood festivals we let people use our factory space to rest with the mikoshi (portable shrines),” Tajima says. “It’s important to us to stay connected with the community—and part of that is passing traditional skills on to the next generation.”

“In 30 years, we want to still be making the same glassware we are today. But to do that, we need to nurture more young artisans. We also need to increase awareness and interest in Edo glass and Edo kiriko. I want to keep this going for as long as I can and pass down the techniques entrusted to us by those who came before.”

By remaining rooted in its community, preserving ancient techniques, and responding to future global needs, Tajima Glass offers a model for how traditional craftsmanship can thrive in the modern world.

Writing: Kiuchi Aki

Photos: Takeshita Akiko

Introduction of the Artisan

Founded in 1956 by Matsutaro Tajima as Tajima Glass Works, Tajima Glass Co., Ltd. adopted its current name the following year, in 1957. For nearly 70 years, the company has been crafting glassware using traditional Edo glass techniques. Its products include Western and Japanese tableware, vases, and, since 2009, Edo kiriko cut glass. One of its most celebrated creations, the Mount Fuji Glass, received high acclaim and was chosen as a commemorative gift for state guests at the G7 Summit in 2016.

・Tajima Glass

・4-18-8 Matsue, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo