Edogawa Craft Stories

Edo Kumiko: The Traditional Beauty of an Intricate Wooden Tapestry

Edo Kumiko

Edo Kumiko Takematsu

Tanaka Takahiro

Tucked into a quiet residential corner of Minami Shinozaki, Edogawa City, the workshop of Edo Kumiko Takematsu quietly carries on a centuries-old craft. Founded in 1982 by Tanaka Matsuo, who trained as a joiner while mastering the techniques of kumiko wooden latticework, the studio is now helmed by his son, Tanaka Takahiro, who has inherited and refined the delicate handwork passed down through generations.

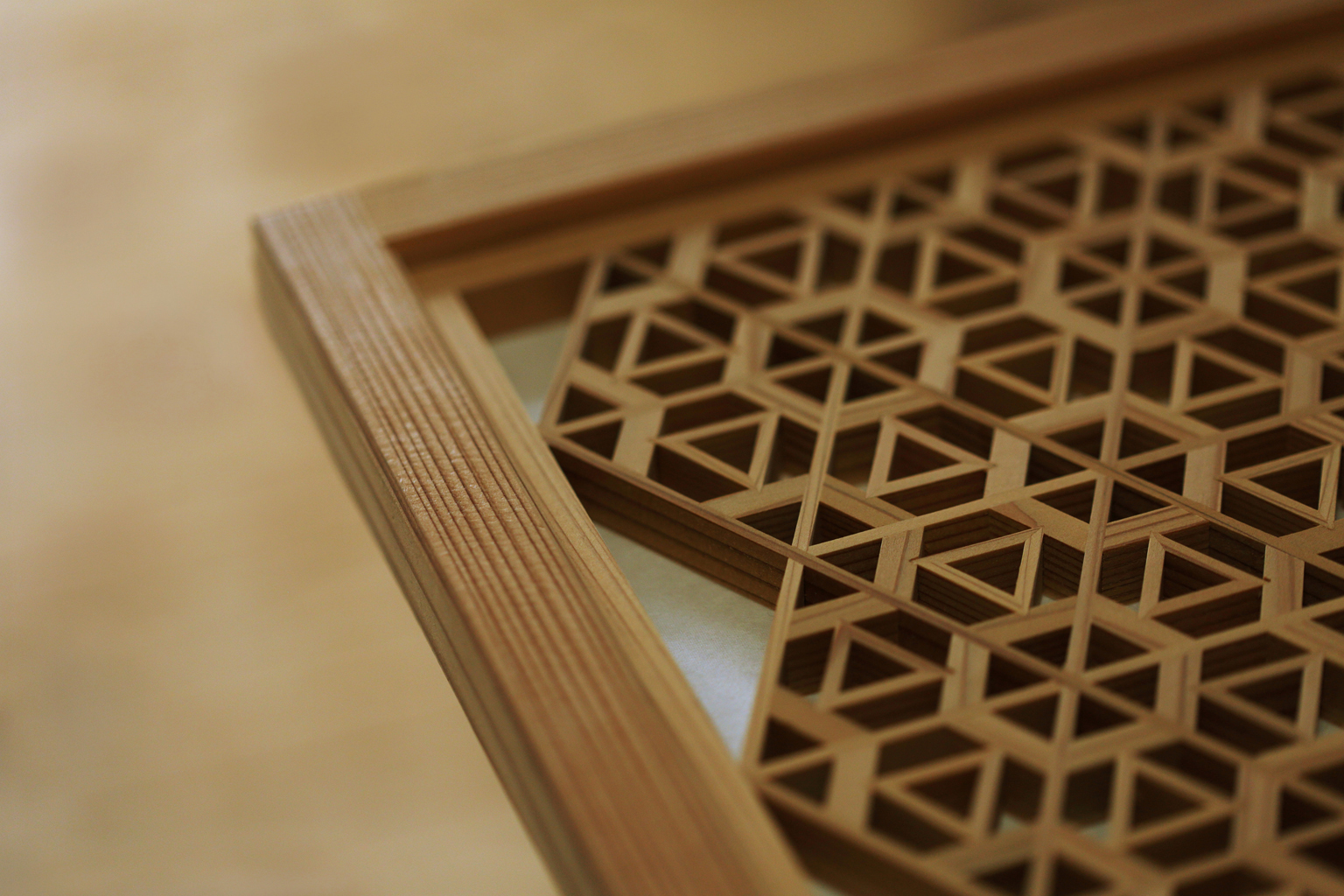

The scent of fresh wood lingers gently in the air inside the workshop. At a central workbench, Tanaka Takahiro is in the middle of slicing narrow slats of timber to create components for kumiko. He works mainly with Kiso hinoki cypress and Akita cedar—fine-grained, high-quality domestic woods that result in pieces that are not only beautiful but durable against shifts in temperature and humidity.

Every component—both the koma (individual wooden pieces) and the surrounding framework—is cut by Tanaka himself from a single board, tailored precisely to the size and purpose of each piece.

Edo Culture and the Rise of Kumiko Latticework in Tokyo

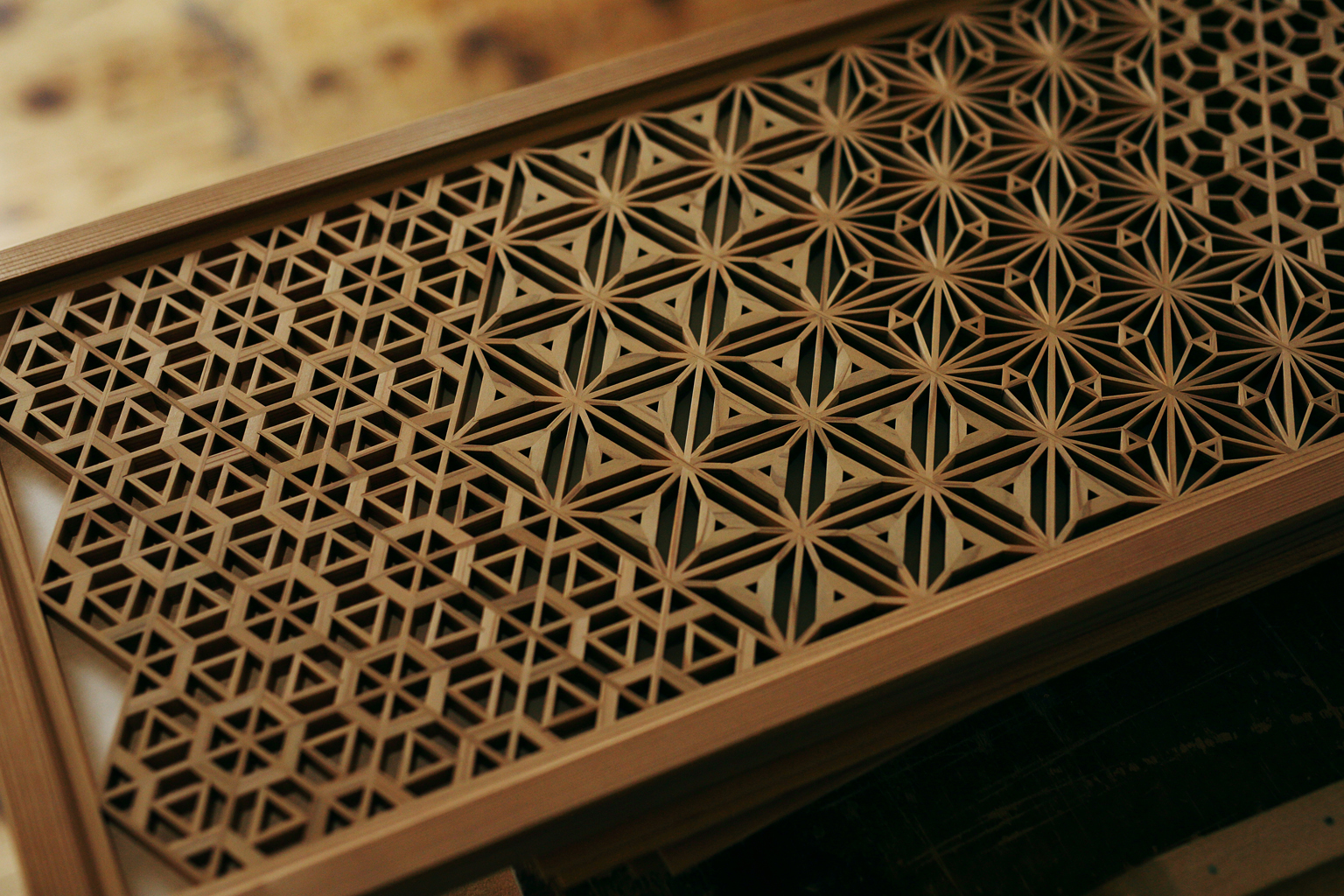

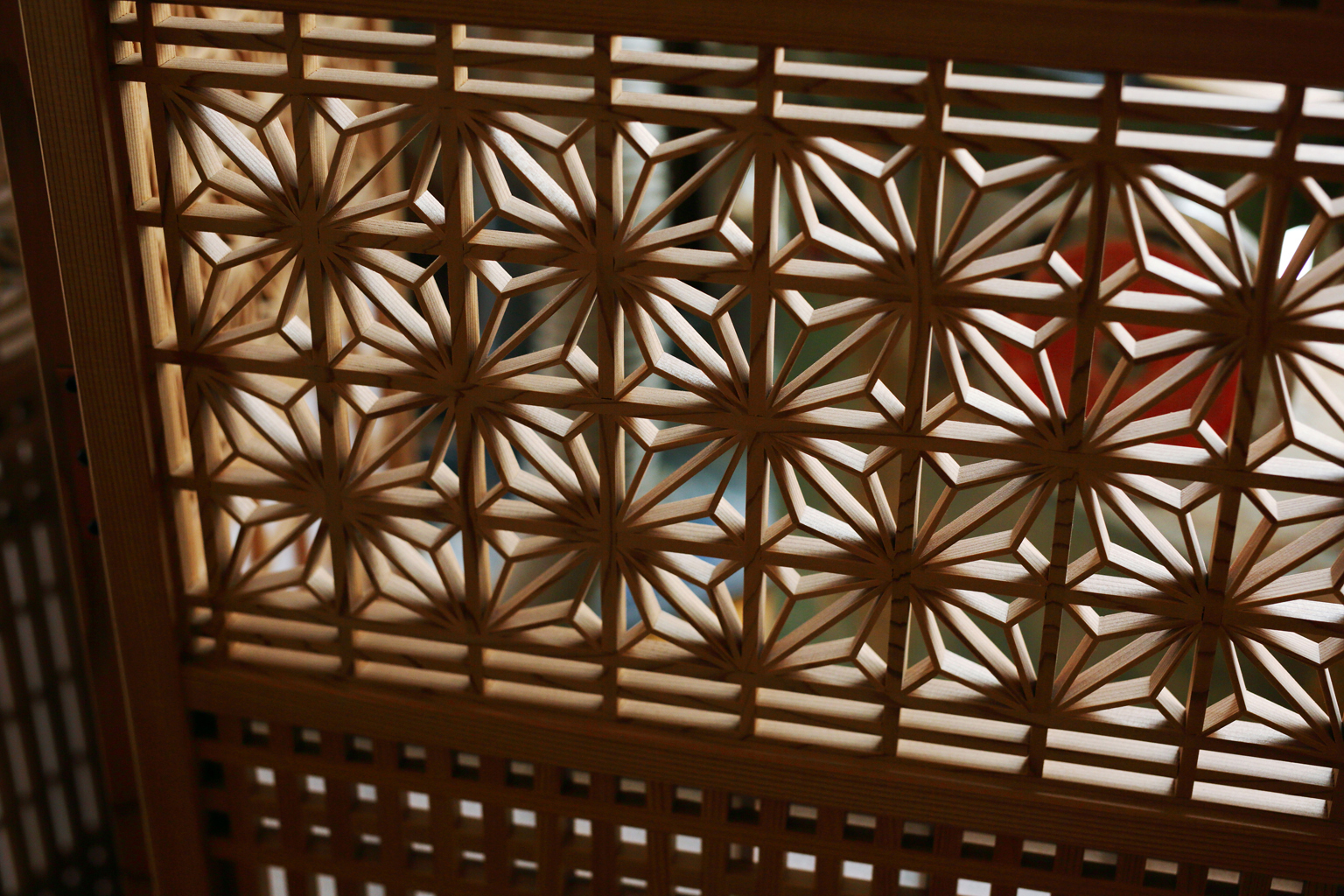

Kumiko is a traditional Japanese woodworking technique in which tiny wooden pieces called koma are intricately fitted together, without the use of nails, to form geometric patterns. Its origins trace back to the late Heian period, gradually evolving as a decorative feature in architectural elements like shoji screens and transoms (ranma).

The craft flourished during the Edo period, when the popularity of wooden architecture surged. As artisans vied to showcase their skills, over 200 intricate patterns were developed, many of which are still passed down today. Each design carries meaning: for example, the asanoha (hemp leaf) symbolizes healthy growth, while the diamond-shaped hishigata pattern is associated with prosperity and lineage.

The hexagonal kikko (tortoiseshell) pattern symbolizes longevity and good fortune. Variations like the snowflake-inspired yukigata kikko add another layer of elegance.

While kumiko is practiced across Japan, the name “Edo kumiko” was coined by Tanaka’s father Matsuo. “Some say the technique evolved more in the countryside because of the frequent fires in Edo,” Tanaka explains. “But Edo had its own tradition, cultivated by the city’s vibrant merchant culture. My father wanted to acknowledge and preserve that legacy by calling our studio Edo Kumiko Takematsu.”

Precision Down to 0.1 Millimeters: The Geometry of Beauty

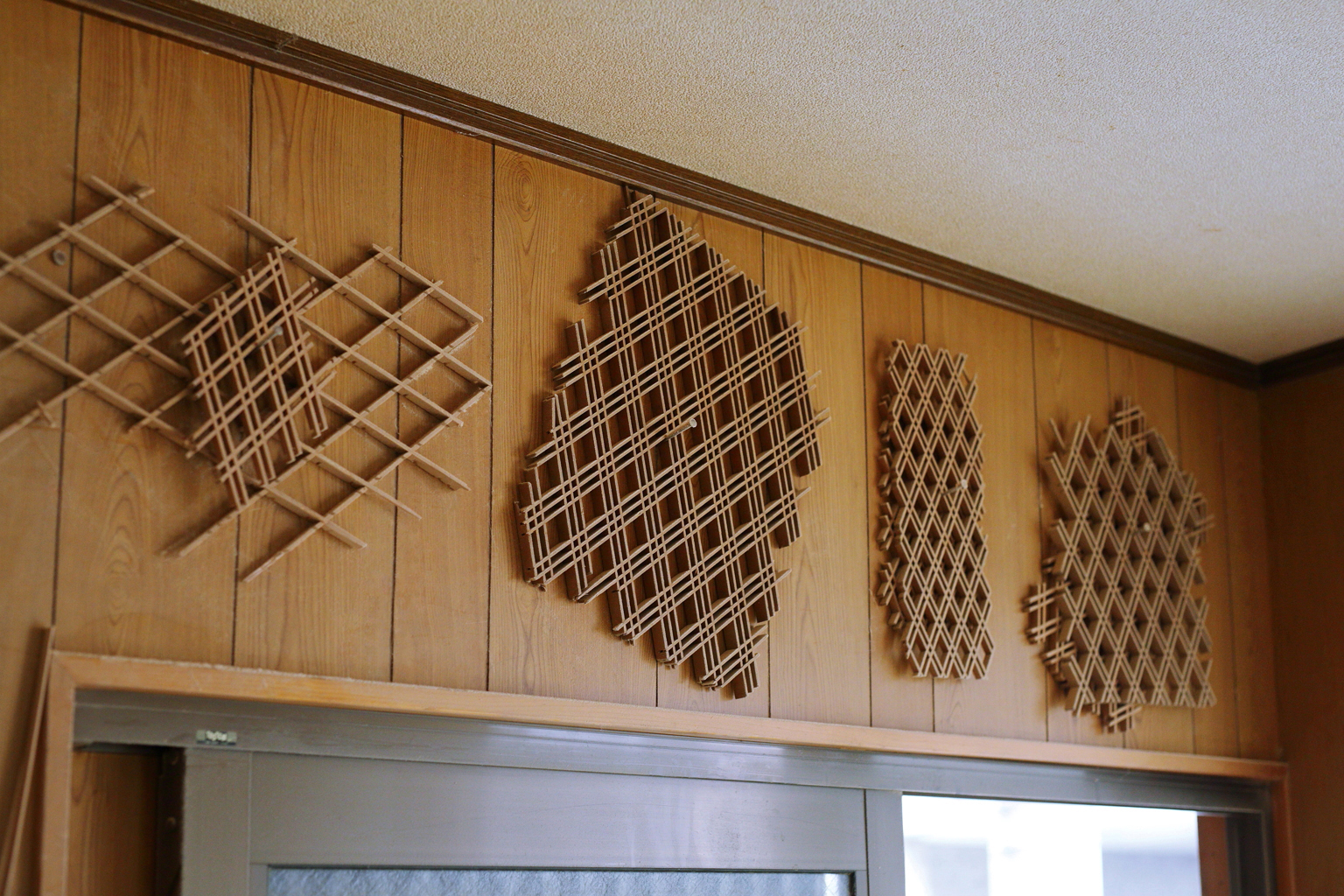

At the workshop, we watched as Tanaka fitted koma into place. In most cases, kumiko is incorporated into pre-sized structures like shoji screens. The process begins with precise measurement and assembly of the outer framework, into which the lattice design is built.

Displayed on the walls of the workshop are foundational styles such as the perpendicular koshigumi and diagonal hishigumi patterns, into which the smaller koma are set.

“When you’re working within a fixed dimension, even a 0.1-millimeter discrepancy can throw everything off. That’s why I use a metal compass to calculate minuscule adjustments and ensure each pattern sits perfectly. It’s probably the most difficult part of all.”

Once cut and planed, each koma must be adjusted to the proper length and angle depending on the pattern. Even the tiniest variation affects the whole design.

Once the layout is finalized, the next step is to cut and plane each individual koma. Their length, shape, and angles are all finely tuned to match the pattern being created.

“Though we do use adhesive, the pieces support each other through precision. When each cut and angle is perfectly calibrated, everything fits snugly into place. Even a small piece like a lantern frame can require over 2,500 components. Some pieces take months to complete, but I work carefully, always mindful of the meaning behind each pattern.”

The wall of the workshop is lined with a range of planes, each chosen for a specific task. “Some of these tools can’t be replaced anymore because their makers have retired,” Tanaka says. “So I take great care of them.”

Across Styles and Borders: The Expanding Appeal of Kumiko

Though kumiko craftsmanship originally developed for traditional Japanese-style rooms, changes in modern housing have opened new doors. As Tanaka explains, this shift has brought fresh energy to Edo kumiko.

“Our most common request is still for shoji in Japanese-style rooms, but lately we’ve been getting more orders from people who want to add kumiko to western-style windows. Some ask us to create folding screens to use as partitions in their living rooms. I’m really happy to see more people bringing Edo kumiko into their homes as part of a modern Japanese aesthetic. I don’t see myself as an artist, but as a craftsman, so my greatest satisfaction comes from creating what people want and knowing they’re enjoying it.”

A folding screen with the asanoha (hemp leaf) motif rests in the studio. Sunlight filters through the intricate pattern, casting soft shadows.

Tanaka is also actively developing new types of kumiko that go beyond traditional architecture and work in everyday modern life. Popular items include tables, TV stands, and andon floor lamps, which project soft, patterned shadows when lit, perfect for showcasing the detailed beauty of the craft.

This andon floor lamp made from Akita cedar is a popular made-to-order piece. Once lit, the delicate patterns gently illuminate surrounding walls and floors.

Global interest in Japanese traditional crafts has also extended to Edo kumiko. At one point, Tanaka collaborated with a Parisian designer to create decorative mirrors featuring kumiko. Another time, an Italian designer overseeing the interior of a global dining chain’s Japan branch commissioned kumiko wall panels specifically from him.

“We’ve hosted workshops at the studio where visitors from abroad make their own kumiko coasters, and they’ve been a big hit. The kumiko lamps are especially popular with overseas guests, many of whom want to take one home. But voltage differences and shipping dimensions are a challenge. I’m thinking about how we can make positive adjustments to allow for international sales.”

A mirror created in collaboration with French designer Nelson Fossey, now on display in the studio. The adjacent shikishi-kake (mount for calligraphy paper) is also a hit with international visitors.

Rooted in Edogawa, Reaching Out to the World

Since its founding, Takematsu has operated out of Edogawa City—a place Tanaka holds dear, having been born and raised there. As he recalls, the landscape of his childhood remains vivid in his mind.

“Things have been redeveloped now, but when I was a kid, there were still thatched-roof houses around here. We had rice paddies, vegetable fields, and even lotus ponds. I’d come home covered in mud every day.”

While the number has dwindled, Edogawa was once home to many small factories and artisans’ studios. Tanaka says the supportive spirit of the community still remains.

“The people here are really understanding of our kind of work. Machines make noise when we’re cutting wood, and I always worry about disturbing the neighborhood—but they’re accepting of it. Thanks to their support and understanding, we’ve been able to carry on this far. It’s a convenient, livable area, and a great place for craftsmanship.”

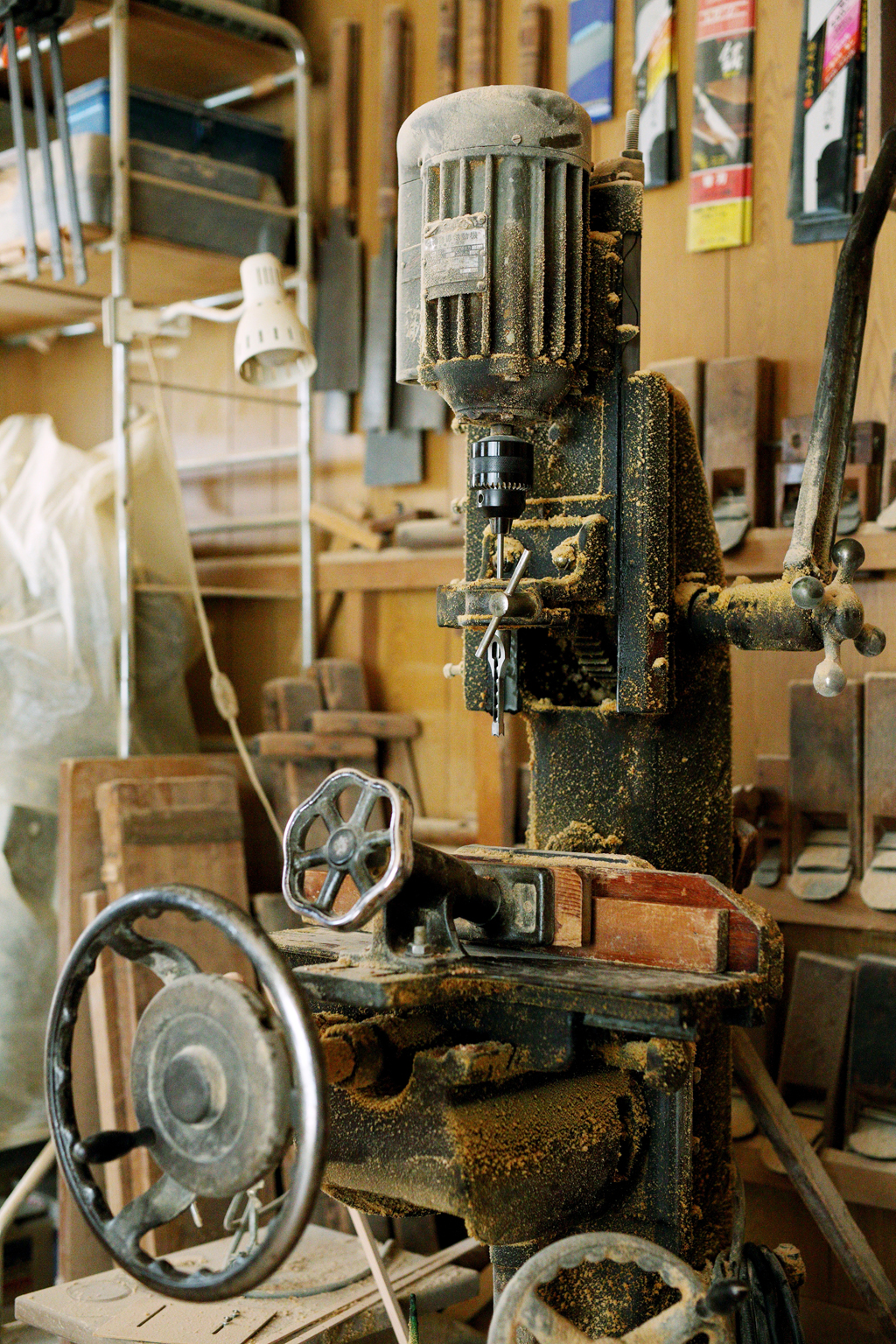

The workshop includes woodworking machines for drilling, cutting, and shaping timber.

When asked about his dreams for the future of Edo Kumiko, Tanaka shares one long-held ambition.

“I studied architecture in college and worked in urban planning before joining my father here. It’s been 25 years now. One dream I’ve carried all this time is to expand overseas, and recently that’s finally started to happen. What’s moved me most is that people abroad aren’t just interested in the final product, they’re curious about how it’s made, the history of kumiko, and the meanings behind each pattern. It’s not just ‘That’s pretty.’ They value the cultural roots. I want to keep making meaningful things and sharing those stories with care.”

Tanaka Takahiro, the second-generation artisan behind Edo Kumiko Takematsu. “No matter how many years pass, making kumiko is still fun. Seeing the joy on a customer’s face—that’s what being a craftsman is all about.”

Rooted in Edogawa and shaped over the course of generations, Edo Kumiko continues to evolve with the times. Its refined beauty and deep symbolism will no doubt continue to resonate across generations and borders.

Writing: Kiuchi Aki

Photos: Takeshita Akiko

Introduction of the Artisan

Founded in 1982 by Tanaka Matsuo, who began his apprenticeship as a joinery craftsman at age 15, Edo Kumiko Tatematsu continues to honor the traditional art of kumiko wood latticework—a craft rooted in traditional shoji screens and transom panels. In 1998, Matsuo’s son, Takahiro, a licensed first-class architect, began his apprenticeship, merging architectural expertise with traditional woodworking. While preserving time-honored kumiko techniques, Edo Kumiko Tatematsu also develops modern lifestyle products, including lighting fixtures and tables. In 2006, Tatematsu’s craft was recognized as an Intangible Cultural Property of Edogawa City.

・Edo Kumiko Tatematsu

・2-20-8 Minami Shinozakicho, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo