Edogawa Craft Stories

Kinako & Mugicha: Listening to the Voice of Soybeans and Barley: Traditional Stone Kiln Roasting

Kinako and Mugicha

Ogawa Industrial

Ogawa Yoshio

The fragrant aroma of roasting fills the morning air at Ogawa Industrial, where soybeans and barley are toasted to perfection in traditional stone kilns. Since its founding in 1908, three generations have upheld this rare roasting method. The reason? It draws out the natural sweetness and aroma of the ingredients like nothing else. We spoke with third-generation president Ogawa Yoshio about the company’s enduring craftsmanship and new ventures.

Located in Edogawa City’s Edogawa—once flanked by the Furukawa and Shinkawa Rivers—Ogawa Industrial is rooted in an area that once thrived on river transport. “Back in the day, the area around the boat docks was lined with tea houses and Western-style eateries,” says Ogawa Yoshio.

“Ogawa Takejiro, the founder and my grandfather, took advantage of the region’s proximity to rice shipments from nearby prefectures. He started the business by making mochi (rice cake) and senbei (rice cracker) dough. Later, he began roasting kinako (roasted soybean flour) and mugicha (barley tea) using a roasting machine. We’re still using the stone kiln roasting method developed back then over a century later.”

Third-generation president Ogawa Yoshio. His upright posture and bright smile leave a lasting impression. “In summer, the factory can reach nearly 50°C when the kilns are running—it takes real stamina. Maybe I stay healthy because I eat so much nutritious kinako and mugicha,” he laughs.

A Second Roast That Brings Out a Deep, Classic Flavor

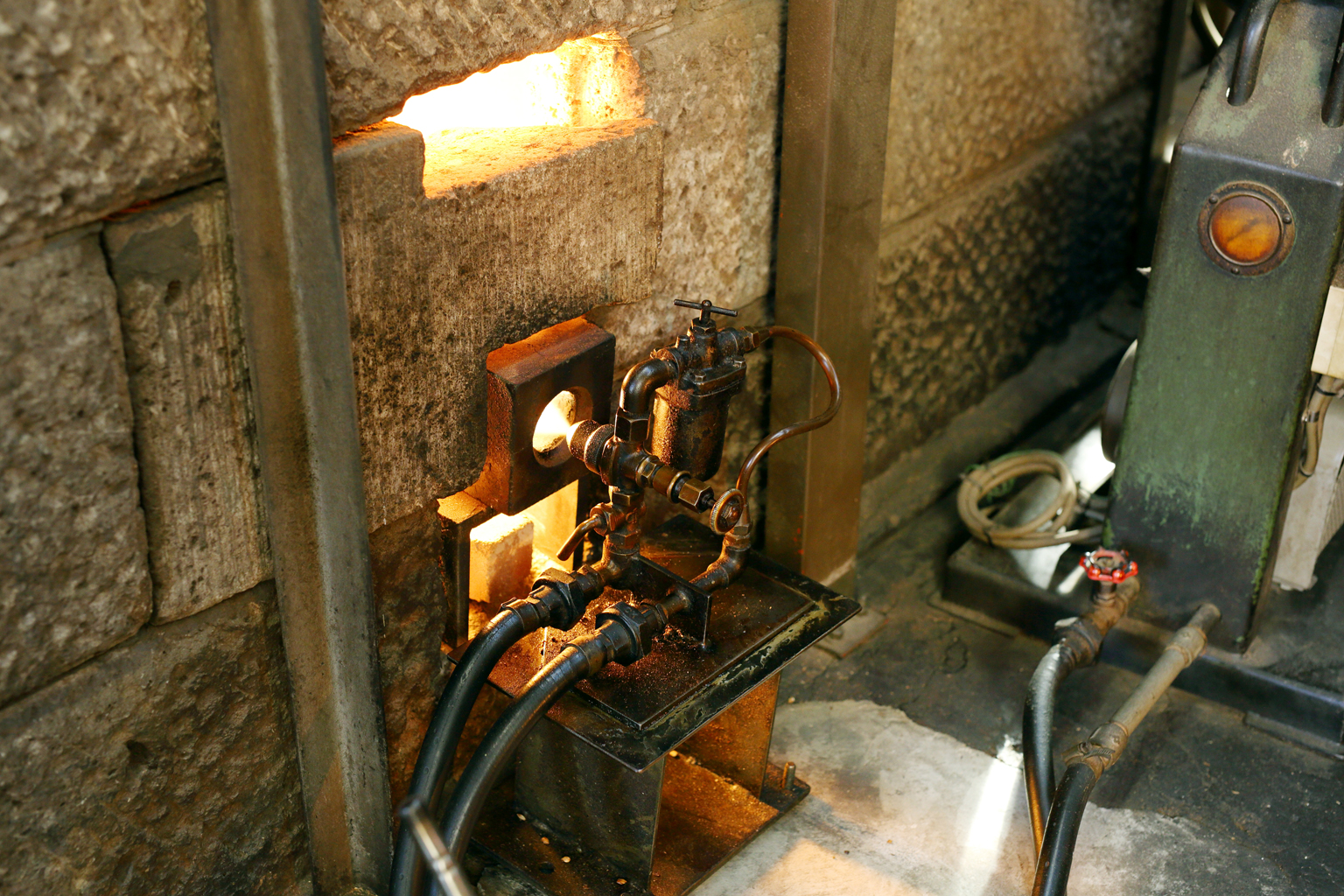

When we visited, kinako was being produced. At the heart of the factory stand two traditional stone kilns. The heavy-oil burners used to light the kilns have been passed down through generations, and unlike modern systems, they don’t have temperature controls. Heat is adjusted manually, by closely observing the state of the kilns.

The inside of Kiln No. 2 glows with flame from the burner, a piece of equipment dating from the Taisho era. Kiln No. 2 itself has been in use since 1956 and is still going strong.

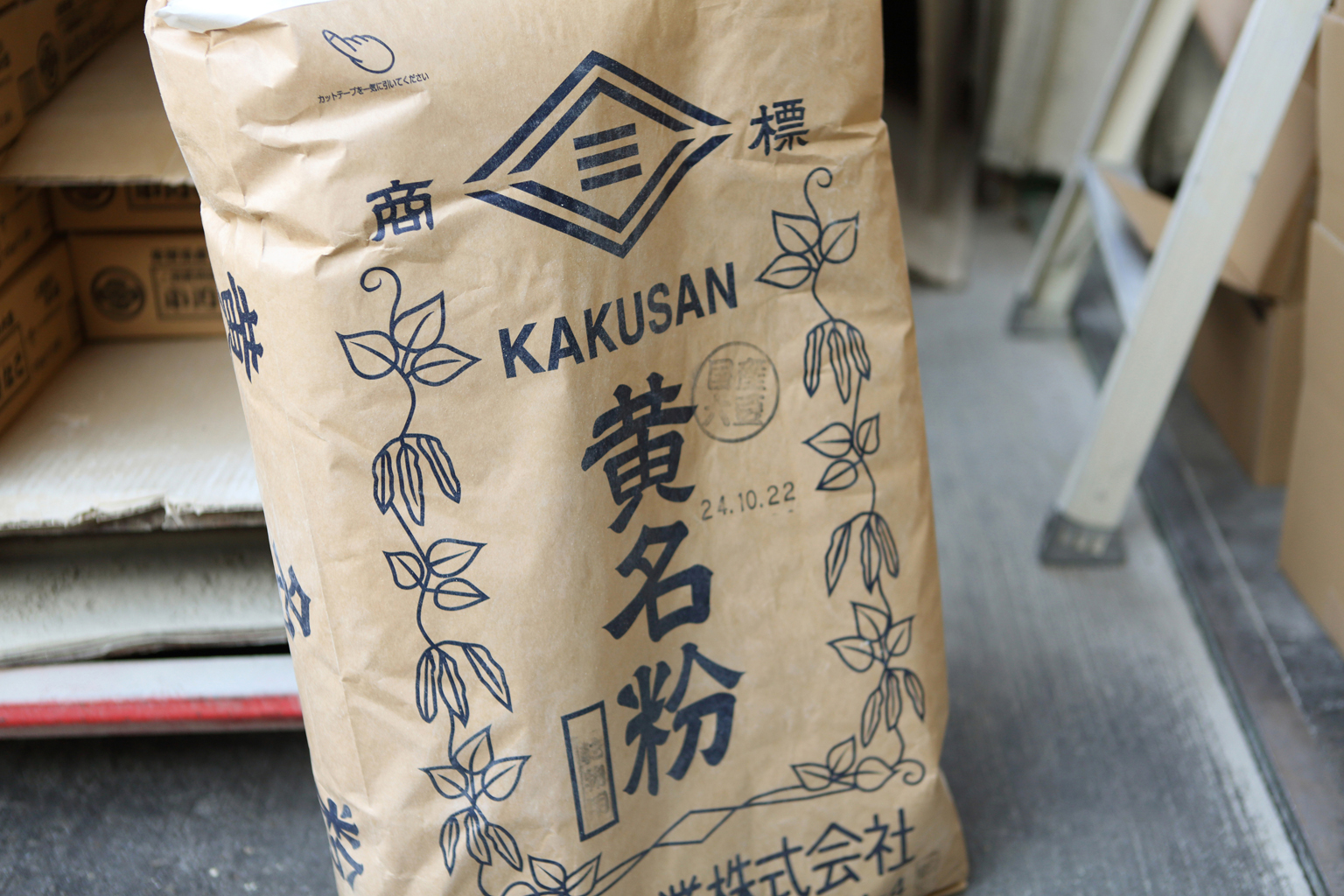

Ogawa’s kinako is made using a unique “double roasting” technique involving both kilns. First, Fukuyutaka soybeans from Saga Prefecture are roasted in Kiln No. 1 at 250°C. Then, the beans are transferred to Kiln No. 2 and roasted again at 180°C.

The kilns feature a dual-layer construction, with an octagonal rotating drum at the center. Unlike a typical cylindrical roaster, the corners help the beans bounce and turn evenly. The outer layer is packed with calcium carbonate sand, which radiates far-infrared heat. This gently envelops the soybeans, coaxing out their natural sweetness and umami. This method was developed through trial and error by the company’s founder in collaboration with a roasting machine manufacturer.

The gleaming silver Kiln No. 1. As the soybeans tumble inside the rotating drum, they gradually turn a rich golden hue.

“Modern hot-air roasters use high-temperature air in sealed chambers for fast roasting and high efficiency. But that sealed environment traps the smoke, which can lead to a smoky flavor. Our stone kilns, made with Oya stone and filled with sand, use far-infrared heat to roast without sealing the chamber. The result is a gentle, thorough roast that brings out a deep, nostalgic flavor.”

Kiln temperature depends heavily on the weather. With no gauges or sensors, how does Ogawa find the “just right” point for roasting? “By using all five senses,” he says cheerfully.

“I listen to the sound of the beans tumbling, watch for color changes, smell the aroma. I even touch and taste them if I need to. After doing this for so many years, I can tell what the beans are ‘saying.’ Whether they’re happy or sad. I read their expression and adjust the roast accordingly.”

Through Hardship, a Constant Pursuit of Better Flavor

Even Ogawa, now a master of the stone kilns, faced many setbacks when he joined the company at age 26.

“My father, the previous president, only showed me how to light the fire. The rest, I had to learn by watching. I even had to figure out machine maintenance on my own—there were times the machinery wouldn’t run because I didn’t know how to oil it properly. I once scorched the equipment by misjudging the flame. But each mistake taught me something. I think that’s how I developed the skill to read the kiln with my senses. Controlling two kilns at once was incredibly difficult at first.”

The factory building was recently renovated, but the original beams and instruments from the old workshop remain on display. “I was told by my grandfather that the beams once belonged to the house where artist Yokoyama Taikan was born,” says Ogawa. The sweat and struggles of his youth are deeply etched into these walls.

Preserving this century-old method of stone kiln roasting hasn’t been easy. During the 1980s bubble economy, while the rest of Japan boomed, changes in consumer tastes—such as the rise of bottled tea and a decline in traditional sweets—caused a steady drop in sales of kinako and mugicha.

“There were some really tough years, but we had loyal customers who valued our flavor. That support reminded me to go back to basics. As a food manufacturer, taste is everything. And to make something taste better, I realized we needed better ingredients.”

That insight led Ogawa to Fukuyutaka soybeans from Saga Prefecture. When he visited the growers, he was deeply impressed by their dedication to soil quality and meticulous crop management, from planting to harvest.

Ogawa Industrial’s classic kinako, Ogawa no Kinako, is made with 100% Fukuyutaka soybeans from Saga Prefecture. Compared to standard soybeans, the variety is higher in protein and stands out for its deep aroma and sweetness.

“By visiting the production region every year and having ongoing conversations with the growers, we deepen our understanding of soybeans. That knowledge gives us real confidence in our products.”

This success with Fukuyutaka soybeans led to the launch of a new product: Dadacha Mame Kinako, made with 100% Dadacha beans from Yamagata Prefecture.

“In Tsuruoka, Yamagata, I met an 85-year-old farmer who still works the fields and mentors dozens of agricultural workers. Inspired by his vitality, I thought, ‘What if we made kinako from Dadacha beans?’—an especially sweet and flavorful variety of edamame. It’s a new kind of value: a kinako made from truly special ingredients.”

By building trust with producers and highlighting the character of each ingredient, Ogawa Industrial has found itself on a new path.

A large-scale milling machine turns roasted soybeans into kinako. Regular maintenance of the central rotating blade ensures the powder has a smooth and silky texture.

Ogawa Industrial’s other flagship product is traditional whole-grain mugicha, a barley tea they’ve made since the company’s founding. Their Tsubumaru® series uses uncrushed domestic six-row barley to avoid bitterness, delivering a clean finish and rich, toasty sweetness.

The Tsubumaru® barley tea series is double-roasted in a stone kiln. Their Tsubumaru® (Soilon) variety comes in plant-derived Soilon filter bags and can be brewed with just hot water—no boiling needed.

“We’ve made small updates, like using tea bags to make brewing easier, but the full flavor and aroma from the stone kiln remain unchanged. Whether it’s mugicha or kinako, our job is to bring out the natural goodness of the ingredients.”

Health Potential Found in Soybeans and Barley

For more than a century, Ogawa Industrial has protected its traditional methods. Today, they’re finding new value in that tradition. One focus for company president Ogawa has been exploring the health benefits of kinako and mugicha. Long called “meat of the field,” soybeans are rich in protein, vitamins, minerals, and fiber. Turning them into kinako, Ogawa believes, makes them a perfect fit for today’s health-conscious lifestyles.

“Kinako is essentially plant-based protein. A study by Kagawa Nutrition University found that our kinako contains all nine essential amino acids the body needs. You can sprinkle it on yogurt or salads, or mix it with cocoa or milk—it’s such an easy way to add high-quality protein to your diet.”

Freshly roasted kinako is ground and packaged right away in the processing room on-site. Truly “just roasted, just made.”

Mugicha also offers health benefits. It contains dietary fiber and minerals, and its signature aroma comes from pyrazines, compounds known to support blood circulation and relieve stress.

“Mugicha doesn’t just promote health—it creates atmosphere. I love how the warm aroma fills a room when it’s boiling. People often associate it with summer, but it’s delicious hot in winter, too. I’d love for more people to enjoy it year-round.”

From the Tsubuko item, which brews in cold water, to the My Bottle Tsubuko for enjoying mugicha on the go, Ogawa Industrial’s lineup suits all kinds of lifestyles.

Rooted in the Community, Looking Toward the World

With the clear appeal of both tradition and health, Ogawa Industrial is now aiming to expand into the Asian market.

In 2014, under an official development assistance (ODA) program from the government, the company helped establish a kinako factory in Sudan. It not only improved local nutrition, but also created employment opportunities—a powerful experience that has influenced Ogawa’s global outlook.

“In Sudan, I saw just how important it is to have access to nutritious food. The situation there is difficult now, so we can’t engage directly at the moment. But I still think—if everyone in the world drank mugicha, maybe we’d all be a little more at peace. Right now, we’re starting by introducing kinako and mugicha to health-conscious consumers across Asia.”

Alongside staple products like Tsubumaru® mugicha and Ogawa no Kinako, the company recently launched a stone-kiln double-roasted chickpea flour. “It’s perfect for vegan and ethnic cuisine, so we’re hopeful about demand in the Asian market,” says Ogawa.

In 2020, Ogawa’s son Keisuke joined the company after working at another firm. Now 116 years since its founding, Ogawa Yoshio hopes the business will continue in Edogawa City and reach its 150th anniversary.

“Our factory produces both noise and smells. Even if people say kinako and mugicha have a ‘nice, toasty aroma,’ it’s still something neighbors deal with every day. We couldn’t have done this without their understanding.”

Keisuke, Ogawa’s son, carries freshly roasted beans in a woven tray in front of Kiln No. 2. He’s now training to lead the next generation of Ogawa Industrial.

Out of a wish to give back to Edogawa, Ogawa also actively engages with the local community—welcoming junior high students for plant tours and job shadowing, and participating in local food education events.

Every morning, the gentle aroma of roasting drifts through the streets of Edogawa—a reminder that Ogawa Industrial’s work, unchanged since its founding in the Meiji era, is still going strong. Holding fast to traditional techniques while creating new value, staying close to its roots while reaching out to the world—their spirit of “one extra step” continues to be passed down, one roast at a time.

Writing: Kiuchi Aki

Photos: Takeshita Akiko

Introduction of the Artisan

Founded in 1908 by Ogawa Takejiro, the company began as Ogawa Shoten, producing mochi (rice cakes) and senbei (rice crackers), before expanding to manufacturing kinako (roasted soybean flour) and mugicha (barley tea). In 1956, second generation Ogawa Shigeo established Ogawa Industrial, with third generation Ogawa Yoshio taking over in 1989. Committed to traditional methods using stone ovens, the company produces signature products like Ogawa Kinako made from 100% Fukuyutaka soybeans from Saga Prefecture and the Tsubumaru® barley tea series, crafted from premium domestic six-row barley. In 2012, they received the Excellent Company commendation in the Edogawa City Industrial Awards.

・Ogawa Industrial

・6-31-4 Edogawa, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo