Edogawa Craft Stories

Honey: The Bees Reveal Edogawa City’s Rich Nature and Blossoms

In the middle of a residential neighborhood in Mizue, Edogawa City, stands a metalworking factory. On its rooftop, a row of beehives buzz with life, as honeybees gather nectar from flowers blooming in parks and along tree-lined streets throughout the city.

y&y honey is a honey brand created by Suzuki Yoshiaki, a lifelong Edogawa resident who runs a metalworks and also works as a beekeeper. His honey, made from the perspective that “to know the flowers is to know the city,” captures the unique and abundant flavor of Edogawa City—a place where urban life and nature coexist.

A First Rooftop Apiary, Born Atop a Metalworks

The apiary for y&y honey is located in Mizue, Edogawa City. Step onto the rooftop of Suzusho Tekko Co., Ltd., nestled among the homes, and the view transforms completely. Bathed in sunlight, planters of herbs and vegetables line the space alongside wooden beehives. It’s a scene of urban rooftop beekeeping that embraces and works with the rhythms of city nature.

Suzuki Yoshiaki, who leads the company, is a true local, born and raised in Edogawa City. In his twenties, he aspired to be a photographer. But after the sudden death of his father in 2000, he decided to take over the family’s metalworking business. His encounter with beekeeping came several years later, in 2007.

“I spent years avoiding the metalwork because I hated it,” Suzuki recalls. “I finally won a photography award—then my father passed away. That was when I resolved to take over the business. Now that I’m creating things myself, I’ve come to find it genuinely fulfilling.”

“I was visiting a photographer friend who lived in Nagano, and their family kept bees. I helped out a bit and suddenly realized: you can make honey yourself. They also worked in magazine publishing, and when they saw my interest, they suggested turning it into a serialized feature—something like, ‘let’s follow your journey learning to keep bees.’ That’s how I got started.”

At the time, Japan was still reeling from the post-bubble economic slump. Orders were down at Suzuki’s factory, which mainly produced architectural metal components like stair railings and handrails. The rooftop of his home, his one place of refuge from the grind of daily work, became his sanctuary. He had already built a pergola and was growing vegetables, so the idea of trying beekeeping there seemed appealing. But it turned out to be much more challenging than he expected.

“One example is swarming, when the bees suddenly take off in a large group to relocate with a new queen. The first time that happened, I had no idea how to handle it—I was completely at a loss. Bees aren’t like pets you can just feed; their biology still holds many mysteries. There are guidebooks out there, but they’re pretty vague. You won’t find practical advice for what actually happens on-site. I’ve seen colonies grow too large, shrink too fast—I’ve been through a lot.”

After much trial and error, Suzuki was introduced to an experienced local beekeeper who generously shared his knowledge. What had started as a casual rooftop hobby gradually took on a much deeper meaning in his life.

There are two main types of honeybees in Japan. The Western honeybee, commonly used in farming for pollination, is the dominant species in beekeeping. Pictured is a Japanese honeybee hive shown to us as reference. Native to Japan, they’re known for being delicate and difficult to raise.

“In my twenties, I loved going to concerts and museums. But when I started beekeeping in my forties, something shifted: I began to feel drawn to the rhythms of nature. I used to think Edogawa City had nothing special to offer, but through the eyes of the bees, I realized it’s actually a place with rich natural beauty despite being part of Tokyo.”

Edogawa City, it turns out, has enough natural resources to sustain beekeeping as an industry. Inspired by this discovery, Suzuki gradually expanded his rooftop apiary.

Now operating under the y&y honey label, he manages 4–6 hives in Edogawa City and 15 more on leased farmland in Ichihara, Chiba Prefecture—producing about 250 kilograms of honey annually.

The rooftop apiary. The square wooden boxes are hive boxes where the bees live. Suzuki has also created a relaxing garden space with a pergola, table, and vegetable planters.

Inside the Hive: A Glimpse at the Bees’ Tireless Work

Suzuki guided us around the rooftop apiary. He lifted the lid of a hive, and the sight of countless bees inside was breathtaking. Watching the constant motion of the bees within their wax combs felt like peering into a miniature city.

Each frame holds around 3,000 bees. Stack several frames and a single hive box becomes home to tens of thousands.

Beekeeping follows a long seasonal cycle. The bees become active in spring, collecting nectar from blooming flowers like rapeseed and cherry blossoms. From spring to early summer, Suzuki harvests the honey, then prepares the hives to ensure the colony can survive the coming winter.

One key task is inspecting the hive frames. Suzuki carefully lifts each one, checking for the queen and monitoring the workers to assess the hive’s overall health.

Suzuki expertly searches for the queen among thousands of worker bees. His hands move with practiced ease.

“The glistening spots in the hive are where the honey is stored,” he explains. “The bees flap their wings to evaporate moisture from the nectar, and once the sugar content reaches about 80%, they seal it in with wax. That’s what we harvest.”

In a bee colony, every individual has a role. Most are female worker bees. Males exist solely to mate with the queen. What’s fascinating is that worker bees take on different tasks each week of their lives.

“When a bee is born, its first job is cleaning the hive. In the second week, it transfers nectar into the comb, mouth to mouth. In the third, it ventures outside to forage. And by the fourth week—its last—it becomes a guard at the entrance. Because a bee dies after it stings, its final role is to defend the hive with its life.”

A honeybee with a ball of pollen nearly the size of its own head near the hive box. A single bee will produce only about a teaspoon of honey in its lifetime.

Even though their lives last just about a month, bees work with fierce dedication. And they don’t gather nectar for themselves alone: the honey is stored for future generations. Suzuki finds this deeply moving.

“Worker bees live short lives and are constantly replaced. But they still collect and store honey not just for themselves, but for bees who haven’t even been born yet. Especially in winter when flowers are scarce, that honey becomes the key to the whole colony surviving until spring. Watching them devote their short lives to something beyond themselves really makes you reflect on how we humans live, too.”

Urban beekeeping offers valuable lessons, but also unique challenges. In a densely populated area like Edogawa City, it’s essential to be mindful of the neighbors.

To that end, Suzuki selects and breeds docile bees, and regularly holds rooftop tours and workshops. He teaches participants how to safely interact with bees, such as not blocking their flight paths or shouting loudly, and promotes beekeeping as an accessible and safe activity for everyone.

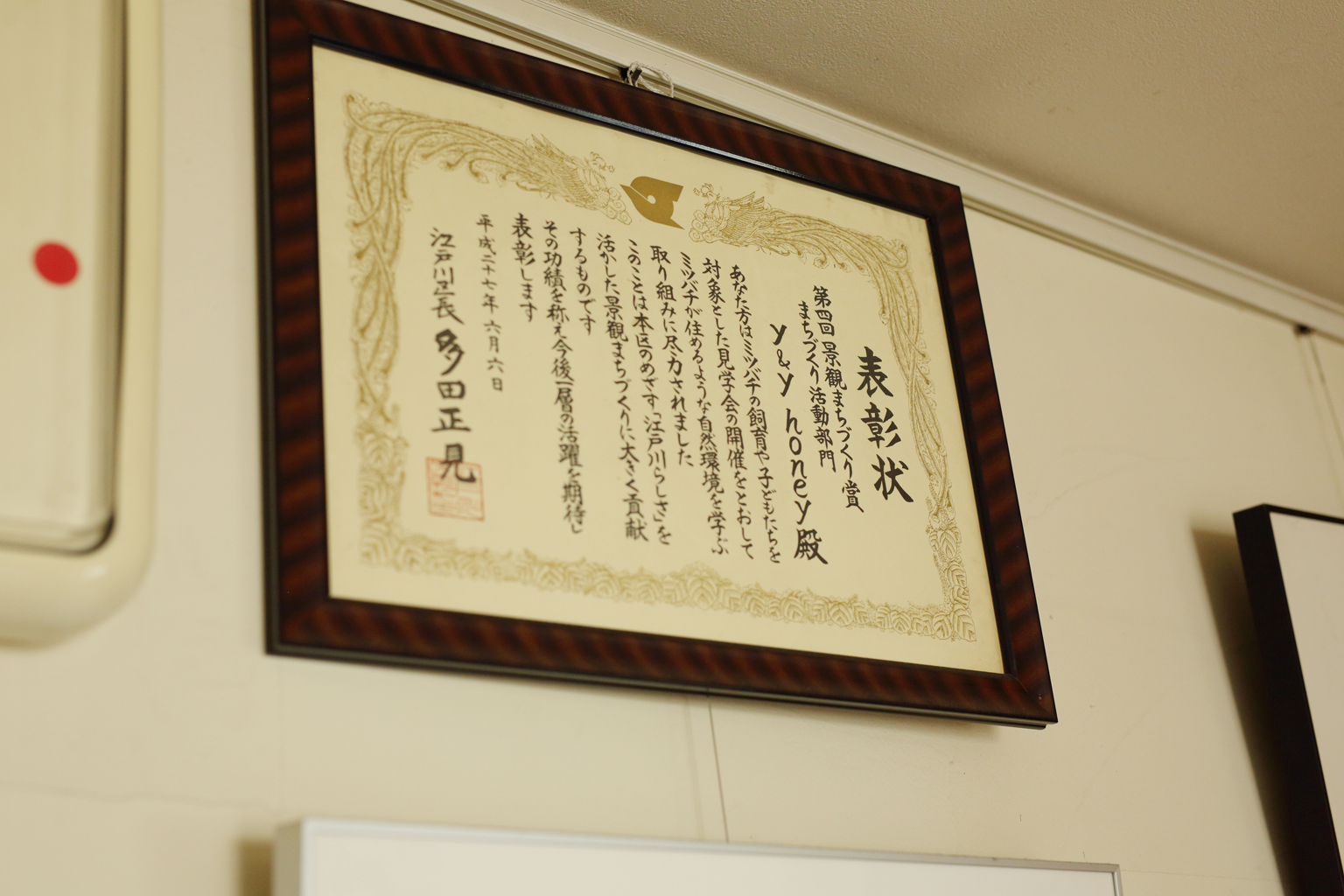

For his work educating Edogawa residents, especially children—, on the natural environments bees need to thrive, Suzuki received a Landscape and Townscape Award from the city.

A Uniquely Tokyo Flavor, Nurtured by Urban Greenery

Since beginning his beekeeping journey, Suzuki’s view of his hometown has undergone a profound transformation. A honeybee’s flight radius is about two kilometers, and in walking through Edogawa City to find nectar sources within that range, he began to see just how much overlooked natural richness the area holds.

“Flowering periods for different plants are listed in field guides, but they won’t tell you where those flowers actually bloom within the city. You just have to walk and find them yourself. Cherry blossoms are easy to spot, but a tree like horse chestnut, which is a great nectar source, isn’t so simple. I spent years exploring to identify all the flowering plants that would become the basis of y&y honey.”

“When you walk around Edogawa,” Suzuki explains, “you notice that newly developed areas and more historic neighborhoods have completely different tree species, placement, and greenery overall.”

“Through those walks I made many discoveries. In spring there’s rapeseed, cherry blossoms, and dandelions; in early summer, tulip trees lining the streets; then in late summer to autumn, flowers bloom in parks and along the riverbanks. In Edogawa City, there’s a seamless relay of flowers from spring to early fall. That continuous diversity is what sustains the bees’ activity.”

The flavor of honey naturally varies between lush rural areas and green-planned urban spaces, Suzuki explains.

“In the countryside, large fields of a single flower variety, like rapeseed, can create quite distinctive, floral honey. In contrast, urban honey reflects the landscape: a blend of many flower varieties, influenced by city planning and green space distribution. The result is a complex, layered taste,” says Suzuki, “People might not normally associate Tokyo with honey, but urban honey has a flavor profile you can’t get from rural regions. It’s got depth, nuance: a taste that reflects the diversity of the city.”

The three jars in the foreground were harvested in Edogawa City. From left to right: May, June, and July. Each month brings different blooms, changing both the flavor and color. That’s the defining character of Tokyo’s multifloral honey.

Reimagining the Relationship between Cities and Nature through Beekeeping

Suzuki’s experiences with rooftop beekeeping have led him to ever-wider natural explorations. Over ten years ago, he began farming in Ichihara, Chiba Prefecture—the same place where he keeps many of his hives. Today, he’s practicing “natural farming,” an approach that avoids both fertilizers and pesticides.

“It’s about nurturing microorganisms in the soil, creating a healthy ecosystem through the food chain. After the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, I started seriously thinking about food safety. I think that’s what really drove me to grow and produce things myself.”

As he spent more time on the farm, he found himself face-to-face with local wildlife, and in particular wild boar damaging his fields. That led him to acquire a hunting license and begin trapping.

“Living in the city, it’s easy to forget that our lives are built on nature’s balance. Through natural farming, you really feel it. Sometimes we do take life to protect crops, but I don’t see it as simply ‘pest control.’ Bees, humans, boars, we’re all part of the same environment. I try to approach every life with that awareness.”

Beekeeping has also become a starting point for connecting city dwellers to nature. Suzuki hosts popular workshops where participants use beeswax harvested from his hives to make items like hand creams and candles, especially popular among women in their 30s and 40s.

A soap made during one of Suzuki’s workshops. It uses beeswax collected from the caps bees make to seal honey into their combs. Bring it close to your nose, and you’ll catch a delicate, sweet scent.

Recently, Suzuki launched a community-based project called “share bees.” The idea is simple: even people who can’t keep hives at home can join in and learn. It’s gaining attention as an accessible way for urban residents to experience beekeeping firsthand.

“We meet about once a month to share beekeeping techniques. It’s a relaxed, easy-going system. Perfect for anyone curious about bees who wants to try being involved.”

For people who can’t realistically keep hives at home, “share bees” offers a way to experience beekeeping and build a foundation of knowledge.

A new connection has also formed between Suzuki’s Ichihara farm and local families from Edogawa City. Some now make regular visits, bringing their children to experience the natural world. Seeing how urban kids respond has made Suzuki even more determined to provide those opportunities.

“Just walking along a forest path brings huge smiles to the kids’ faces. But unlike my generation, who ran wild on riverbanks, today’s kids don’t always know how to play in nature, even when they’re surrounded by it. That’s why I want to give them more chances to connect with the outdoors.”

In addition to his work with bees, Suzuki continues to create furniture through f926, a brand he started before beekeeping. Drawing on his background in metalwork, he combines steel and wood into pieces that reflect the joy of making things by hand.

A chair from Suzuki’s furniture brand f926, placed quietly on a terrace.

Looking ahead, Suzuki dreams of opening a brick-and-mortar y&y honey store in Edogawa City. More than just a sales space, he envisions it as a gathering point for people interested in beekeeping, nature, and sustainable living. He also hopes to raise the profile of Tokyo-made honey more broadly.

“One day I’d love to take part in a market overseas, selling honey directly. Tokyo’s honey isn’t well known yet, but I’d love to share its unique flavor with people—not just in Japan, but all around the world.”

From the rooftops of Mizue to farms in Chiba, the ripple effect of Suzuki’s beekeeping continues to grow—bridging communities, cities, and nature.

Writing: Kiuchi Aki

Photos: Takeshita Akiko

Introduction of the Artisan

In 2007, Suzuki Yoshiaki began beekeeping on the rooftop of Suzusho Tekko metalworks in Mizue, Edogawa City, leading to the start of the y&y honey commercial brand. In 2010, he expanded to a second apiary in Ichihara, Chiba Prefecture, and began seasonal hive transfers. Today, the honey is harvested at three sites: Mizue (Edogawa City), Ichihara (Chiba Prefecture), and Fuji (Shizuoka Prefecture). Since 2013, Suzuki has also practiced natural farming and hunting near the Ichihara site, living a dual-location lifestyle.

・y&y honey

・1-2-15 Mizue, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo