Edogawa Craft Stories

Blueberries: Blueberry Farm Tokyo’s Challenge to Reimagine Urban Agriculture as a Sightseeing Farm

In the Edo period, Higashi-Koiwa in Edogawa City flourished as a key point for river transport connecting urban and rural areas. Today, on the banks of the Edogawa River at the Tokyo–Chiba border, you’ll find Blueberry Farm Tokyo, which cultivates over 30 varieties of blueberries—the most of any location in Tokyo’s 23 cities.

Opened in 2023, Blueberry Farm Tokyo offers a luxurious experience: freshly picked blueberries, right in the city—just a 35-minute train ride from JR Tokyo Station. It’s also Edogawa City’s first sightseeing farm. The driving force behind this new venture is Yano Takayuki, the 17th-generation farmer of a family that has long called the area home. Amid ongoing urban development, Yano chose to preserve the family’s farmland, where his grandparents once grew komatsuna (Japanese mustard spinach), and to cultivate a wide range of blueberries as a new form of urban agriculture.

From Komatsuna to Blueberries: A 17th-Generation Decision

Stepping into Blueberry Farm Tokyo, you’re greeted by the impressive sight of around 1,000 neatly planted blueberry bushes. Though Edogawa City is one of Tokyo’s more agriculturally active wards, this is its very first sightseeing farm. Since opening in 2023, it has hosted a hands-on “pick-your-own” experience, where visitors can sample and harvest berries to pack and take home. From early June to mid-August—peak blueberry season—families and local residents flock to the farm in search of ripe, juicy fruit.

The man behind this project, Yano Takayuki, comes from a long line of farmers in Higashi-Koiwa.

Yano, who had been working in the private sector after completing graduate school, decided to take over the family farm at age 30 when his grandfather, who had long grown komatsuna, suffered a stroke.

“My parents didn’t continue the farming business, and when my grandfather retired, there were even suggestions to turn the land into apartment buildings. But I just couldn’t let all of my grandfather’s passion and hard work go to waste, especially after growing up so close to it. Still, with no farming experience and about 2,000 square meters of land, the big question was: what could I realistically grow on my own?”

Feeling the challenges firsthand, Yano spent two years visiting farms and sightseeing orchards around Japan. Eventually, he realized the farm’s excellent location, just 35 minutes from central Tokyo, could be the key to its future. If he could create an agricultural experience with added value, he might find a way forward.

He considered various options, from strawberries and melons to grapes and pears, but ultimately chose blueberries.

“Blueberries are low growing, so they’re easy to pick even for children and elderly visitors. Plus, the main harvest season from June to August overlaps with summer vacation, which I thought would appeal to families in the Tokyo area.”

At the time of the interview, the blueberries were still green. Over the weeks ahead, they would gradually ripen into plump, vibrant fruit.

Yano says his family initially had concerns: “Why blueberries?” “Is there even a demand?” Still, he persisted, explaining his vision and the unique qualities of blueberries. He told them, “If I don’t take this chance, we won’t be able to preserve the farmland.” Even his hospitalized grandfather, unable to speak due to the stroke, gave a supportive nod when Yano shared his plan, giving him the final push to move forward.

One of the farm’s most distinctive features is its incredible variety: over 35 types of blueberries—the most in all of Tokyo’s 23 cities. While most of us only see a few kinds of blueberries in supermarkets, the reality is far more diverse, explains Yano.

“Before I started this, I thought there were maybe four varieties,” Yano laughs. “But there are actually 400–500 varieties still in existence. It’s a world more like flower breeding than fruit farming.”

One of the cultivars grown by Yano is “Titan”—a large, richly flavored berry several times the size of the standard Japanese supermarket kind, often reaching the size of a 50- or even 100-yen coin. Because nutrients concentrate at the branch tips, carefully pruning the branches improves both fruit size and flavor. (Photo courtesy of Blueberry Farm Tokyo)

Each variety stays ripe and flavorful for only about three weeks, so Blueberry Farm Tokyo strategically staggers the harvest seasons. By cultivating a wide range of varieties, they can stay open and harvesting for several months.

The Strengths of a City Sightseeing Farm That Offers Rare Varieties

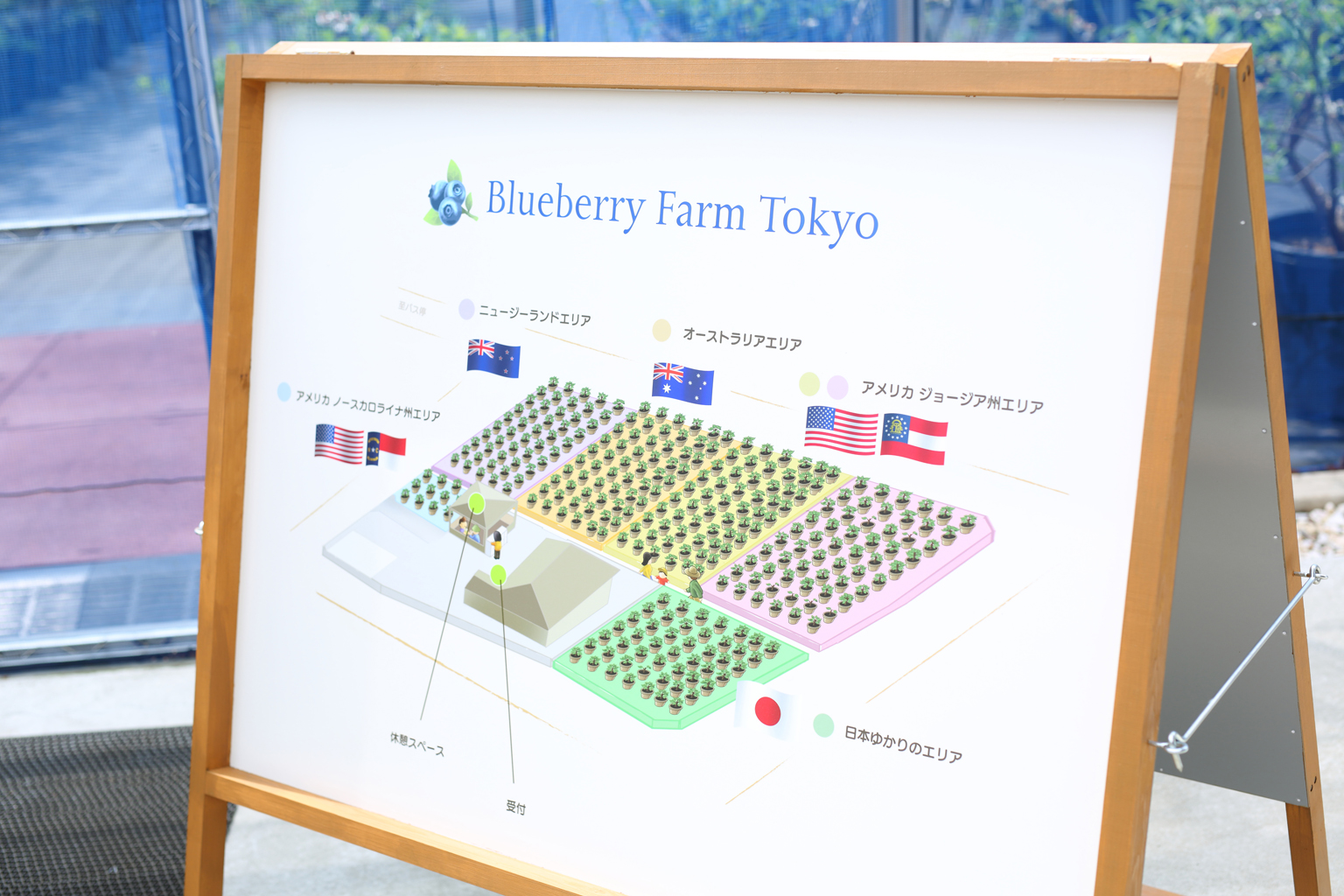

The farm is divided into six zones, with color-coded pots for the different blueberry plants.

These color codes serve two purposes. First, to help visitors navigate: the pots’ colors correspond with the map, making it easy to tell where you are. Second, for managing harvest timing across the many varieties.

Yellow for Australia, pink for Georgia, USA—just by looking at the pots, you can tell where each blueberry cultivar originates.

“Blueberries fall into three main groups: Southern Highbush (for warm climates), Northern Highbush (for colder regions), and Rabbiteye. We’ve sourced many varieties from the US, New Zealand, and Australia, and arranged the zones so each ripens at a different time. That way, visitors can enjoy picking blueberries over a span of more than three months. Each zone also features flags showing the varieties’ countries of origin, so you can learn a bit about their background.”

The farm’s area map includes American, New Zealand, and Australian varieties, as well as a section for Japanese blueberries.

Visitors to the farm walk between rows of pots to pick the berries, but there’s a twist: instead of planting one variety per row, as most sightseeing farms typically do, Yano has mixed several into each row.

“Having just one variety per row makes things easier for the farm, but it means visitors have to move to another row to try something different. By planting multiple varieties in each row, people can sample several types just by walking along a single path. And with summers getting hotter, it’s a more comfortable experience.”

Originally native to North America, blueberries were a staple food for Native Americans. Over time, cultivation programs around the world have created countless new varieties. In the US, the trend now favors large, thin-skinned, juicy blueberries. But in Japan, most of what reaches store shelves are smaller, thick-skinned “classic” varieties.

“Thin-skinned blueberries don’t travel well, so they aren’t ideal for long-distance shipping. That’s why Japanese supermarkets mainly carry the firmer, smaller classic types. But since our farm is right here in Tokyo, we can grow large, premium varieties and let people enjoy them fresh—something they probably don’t get to do very often.”

Every blueberry plant at the farm is labeled with its variety name. Shown here is “Sharpblue,” developed by breeder Dr. Sharp and said to have revolutionized the blueberry industry. (Photo courtesy of Blueberry Farm Tokyo)

Supported by the Community, Overcoming the Challenges of Cultivation

As you walk through the farm, you might spot a chubby black-and-yellow bumblebee (Bombus ignitus) leisurely flitting from one blueberry blossom to another. These bees are kept specifically for pollination and are said to be over ten times more docile than honeybees, almost never stinging unless provoked.

A bumblebee perched on a blueberry flower. “Thanks to them, we can count on a bountiful harvest,” says Yano.

Once pollinated, the flowers turn upward, and the petals gently fall away to make room for the fruit.

You’d never guess from the peaceful atmosphere, but getting Blueberry Farm Tokyo to this point involved no small number of struggles. One of the biggest obstacles? Japan’s soil isn’t naturally suited to blueberry cultivation.

Blueberries require plenty of water, but paradoxically, they also need well-drained soil. That makes many varieties hard to grow directly in the ground in Japan. To solve this, Yano chose to grow everything in pots. The ground is also covered with weed-control sheets, which serve more than just aesthetic purposes.

“Some of our visitors from central Tokyo are hesitant about getting their shoes muddy. But with these sheets, the ground stays clean and walkable even in light rain. That made a huge difference.”

To further streamline operations, Yano introduced a fertigation system that automatically delivers water and nutrients to each pot. Thanks to this setup, he’s able to handle the heavy demands of watering and fertilizing entirely on his own.

Each pot has its own hose, through which a custom fertilizer-and-water solution is misted in precise amounts suited to the variety.

Even with this level of automation, though, there were times when the work was simply too much for one person. One of the biggest challenges came during the setup: filling an enormous number of pots with soil.

“We had to transplant every seedling into a pot while the blueberries were dormant in winter. That meant filling 800 large 60-liter pots, plus 200 smaller ones—1,000 in total. Preparing that much soil on my own was physically impossible. I hit a wall and ended up reaching out to all my childhood friends from the neighborhood.”

To Yano’s surprise, many of them showed up. One even took 10 days off work to help, saying, “If Yano’s in trouble, I’ve got to pitch in.”

Transplanting blueberries into larger pots once they’ve matured is a familiar winter task for blueberry growers.

“I can never thank those friends enough. In fact, some of my old elementary school classmates still help out today. When transplanting season comes around, they’ll say things like, ‘It’s about time for Yano’s replanting, isn’t it?’ and come lend a hand.”

This spirit of support extends beyond friends.

“My mother would offer taste samples to early morning walkers during the farm’s early days, and local restaurants helped by putting up posters,” says Yano. A retired carpenter who was a friend of Yano’s late grandfather now builds wooden tools for the farm and even assists with visitor guidance and blueberry packing. “Taking over the farm really made me appreciate how deeply connected we are to the community,” Yano reflects.

Passing It On: The Role of Urban Farmland in the Next Generation

With support from those around him, Yano has carved a new path as a sightseeing farmer. But his mission goes beyond simply offering delicious fruit; it’s about raising awareness of why farmland still matters in a city.

“In a big city like Tokyo, if a major earthquake hit and transport stopped, food supply would quickly become an issue. But if farmland remains, it could provide food, at least temporarily, for people nearby. That kind of peace of mind is one of the vital roles of urban farming.”

Unlike vast rural farms, urban farmland sits close to where people live, which makes it easier to connect with residents. Yano sees this as a chance to build stronger communities. Much like the bonds he’s forged with old classmates through the farm, he hopes to use agriculture to bring people together. He’s also exploring how farming can support food and environmental education for children. Currently, he is working to host local elementary school students for extracurricular programs, teaching them how blueberries grow and fostering awareness of the natural environment.

Yano explains the origins of blueberries using a map of North America, where the fruit is native.

“As the 17th-generation farmer of my family in Edogawa City, I feel it’s my duty to pass down what I’ve inherited in the best possible form. That doesn’t just mean protecting our farm, but also preserving this region’s history, culture, and community for the next generation.”

There are currently 266 farming households in Edogawa City, but with aging farmers and a lack of successors, the future of local agriculture is far from certain. Yano’s commitment to sharing the story of his farm is rooted in a desire to raise awareness, not just to promote his own venture, but to show the importance of urban farming as a whole.

“If people knew that running a sightseeing farm was one way to carry on agriculture, maybe more would consider taking over. If my experience of inheriting my grandfather’s land and finding a new direction can help other farmers, I’d be thrilled. I’ve heard that Higashi-Koiwa once prospered as a key hub connecting Edo and the countryside. In a way, I want to carry that forward, creating new human connections through this urban farm.”

From the lush, thriving blueberry bushes in Edogawa, a glimpse of the future of agriculture in Tokyo is revealed—and of the vital role it can play in supporting the city’s way of life.

Writing: Kiuchi Aki

Photos: Takeshita Akiko

Introduction of the Artisan

A city-based sightseeing farm opened in 2023 by 17th-generation farmer Yano Takayuki in Higashi-Koiwa, Edogawa City. Making use of the land where his grandparents once grew komatsuna, Yano now cultivates around 35 varieties of blueberries—more than anywhere else in Tokyo’s 23 wards. Some rare varieties not typically seen in Japan are available to taste. Just 35 minutes from Tokyo Station, the farm offers pick-your-own and direct sales from early June to mid-August. With pot cultivation and an automated irrigation system, the farm brings new possibilities to urban agriculture.

・Blueberry Farm Tokyo

・2-20-3 Higashi-Koiwa, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo