Edogawa Craft Stories

Crafting Original Edogawa Ceramics from Koiwa Soil

Kouwayaki Reishiyou / nicorico

Hayashi Nobuhiro and Hayashi Ayako

“Kouwayaki” is a style of ceramics born and rooted entirely in Tokyo—more precisely, in Edogawa City. What makes it unique is that the clay comes directly from local soil excavated in Koiwa. It’s a ceramic ware that quite literally could not exist anywhere else. Over 50 years ago, Hayashi Nobuhiro, the founder of Kouwayaki, began making pottery using this distinctive Kouwa soil, named after his hometown of Koiwa. He later coined the name “Kouwayaki” for the pieces he created.

What started this journey was remarkably simple.

“When I was a university student, I saw a Living National Treasure working the potter’s wheel on TV. I thought, ‘That looks fun—I want to give it a go.’ That’s all there was to it.”

But this was over half a century ago; there was no internet, and hardly any specialized books on ceramics in bookstores. Still, with just a few pages from an old secondhand manual, Hayashi began to teach himself the craft. The first challenge: finding clay.

“I didn’t know where to buy clay, so I figured I’d try using the dirt from my own backyard. I remembered from when I was a kid that if you dug down, you’d eventually hit clay.”

However, he quickly discovered that Tokyo’s soil had long been considered unsuitable for ceramics. The ground in Tokyo is part of the , a layer created by mainly ancient volcanic ash from eruptions of Mt. Fuji and Mt. Hakone. It’s high in iron and alkaline content, and has low fire resistance.

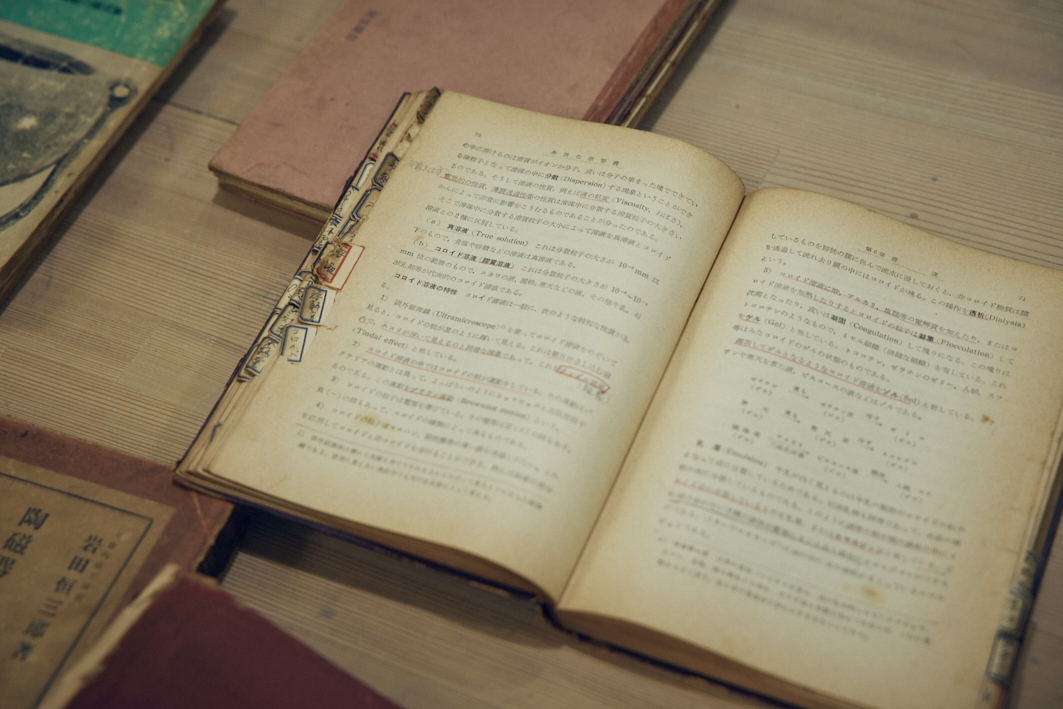

“Low fire resistance generally means it’s no good for pottery. But I wanted to work with this soil. Even if everyone said it wasn’t right for pottery, I thought, maybe if I experimented enough, I could make it work.” From his workshop, Hayashi pulls out a well-worn chemistry textbook and stacks of notebooks detailing countless clay and water ratios.

“There was no one to teach me. All I could do was try, fail, and try again. Oddly enough, an old high school chemistry textbook turned out to be pretty useful.”

The chemistry textbook Hayashi relied on in his early days, covered in red underlines and sticky notes.

Even with clay deemed subpar for ceramics, he believed that with proper refinement and careful control of firing temperatures, it could still be used at high heat. Eventually, Hayashi left university to devote himself entirely to ceramics. Years of obsessive research and trial-and-error paid off—he successfully fired ceramic ware at over 1,100°C, a high-fire temperature.

He named this style Kouwayaki, after “Kouwari,” the name Koiwa was believed to have during the Nara period. That historical echo resonated with him and shaped the identity of his work.

In 1981, at age 35, one of his Kouwayaki jars was accepted into the Japan Ceramic Art Exhibition for the first time. “I’d been wrestling with this soil for over a decade by then,” he laughs. “To see what I believed in finally acknowledged meant a lot.”

Hayashi at the wheel. Though it looks easy, success depends on perfect coordination between palms, fingertips, and even room temperature. It’s a skill forged over years of working with clay.

Today, Hayashi continues to blend traditional ceramic techniques with his own innovations.

One standout is his Kouwado Kaishoyaki pottery, which has a rough surface and a smoky, dark-brown iridescence that gives it a mysterious charm. This effect is created by a unique method he developed: placing shells near the pottery in the kiln. As the shells burn, the gases released react with minerals in the clay to form unpredictable, cloud-like patterns. Another piece, the Kouwado Hakuyu (white-glazed) sake cup evokes freshly fallen snow with its soft, pure-white finish. The glaze is Hayashi’s own formula, applied to clay he dug up in 2017 when renovating the workshop and refined meticulously over three years. There’s also Benisanyu, a glaze that shimmers in iridescent hues, developed through his own proprietary blend.

“I love experimenting, mixing this and that and seeing what happens in the kiln. I’ve had my share of failures, but I’ve never once thought about quitting,” he says with a smile. His eyes light up as he shares one creation after another. There’s a playful warmth to his work, infused with the spirit of Koiwa’s soil.

A sake bottle and cup in the Kouwado Kaishoyaki style. The dark, glossy areas were formed by gases emitted from burned shells.

A flower vase made from Koiwa soil. Its classic earthy brown is offset by diagonal white stripes, giving it a modern edge.

The Kouwayaki Reishiyou workshop and storefront, just a few minutes’ walk from JR Koiwa Station, has been a fixture since 1972. Hayashi remodeled his childhood home with his own hands, converting a tiny three-tatami-mat workspace and a six-mat shop into a functioning studio. Over the years, it’s grown into a handsome, gallery-like space marked by deep brown walls and brick tiling, reflecting the very earth from which it was born.

And in this same studio now works his daughter, Ayako Hayashi, who began her own ceramics practice in 2005. “I grew up watching my dad work, but I never thought I’d become a potter myself.”

She studied architecture in vocational school and worked in architectural design and construction management. But in her late twenties, she began wondering what she could do that was unique to her.

“For some reason, my dad’s work was the first thing that came to mind. Around that time, I was also building a website for Reishiyou, and the more I researched his work, the more I realized how deep and fascinating pottery could be. Still, having seen how much he struggled on his own, I knew this wasn’t something to take lightly. I talked to a friend about it, and they just said, ‘You’ll never know until you try.’ So, I started making pieces bit by bit on my days off.”

She began by learning to throw on the wheel, but months passed without progress. “I’d get frustrated thinking, ‘Why is it so easy for Dad and so hard for me?’ But he’d say, ‘There’s no one right way—you have to figure out how to shape things using your own fingers and instincts.’ He never really gave me direct instructions.”

For months, she repeated the cycle of shaping and destroying pieces. About six months in, her father finally broke the silence: “Maybe it’s time you tried firing one.”

Though she still kept her day job, she began crafting pieces closer to her current style. She created her own website and uploaded photos—and then one day, a Tokyo gallery reached out: “Would you like to hold a solo exhibition?” In 2006 came a turning point—her first show.

Loading the kiln. “It’s nerve-wracking every time—you never know if a piece might crack or collapse,” says Ayako.

“To have total strangers look at something you made and love it enough to buy it… I was deeply moved by that. I thought, ‘If I keep going, I might be able to create something truly unique to me.’”

In 2008, she left her job to focus fully on ceramics and launched her brand, nicorico.

Ayako’s concept is simple and heartfelt: “I want people who cherish the little things in daily life to smile—nicori—when they use my work.” Her pieces combine traditional techniques like kakiotoshi or sgraffito (scraping away layers of slip to create patterns) with her own flair. The Monka Saidei Hikiotoshi series features vibrant, pop-inspired designs that remain elegant enough to blend into any interior.

Where her father’s pieces are earthy and weighty, Ayako’s are lively and bright—something you could happily keep on display forever.

Carving patterns using the traditional kakiotoshi method. With no sketching beforehand, she draws intricate designs directly—before the clay dries out, requiring speed and precision.

“I want to make everyday tableware and accessories that feel special—not too fancy, but unique. Things that aren’t mass-produced, but not overly precious either—just ‘a little something nice’ for daily use.”

Both father and daughter share a single-minded devotion to their craft. In that way, they’re more alike than they may realize.

Ayako’s colorful nicorico soba cups. A stark contrast to her father’s work, with charming patterns created through kakiotoshi and vibrant colors.

Text: Makino Yoko

Photos: Honna Yuka

Introduction of the Artisan

Founded in 1972 by Hayashi Nobuhiro, Reishiyou is a pottery studio born from years of dedicated research and creativity. Hayashi successfully crafted ceramics using natural clay from his hometown of Koiwa, in Edogawa City, naming it “Kouwayaki.” His daughter Ayako continues the family legacy through the brand nicorico, a vibrant, everyday-friendly line of pottery. Their studio and store are located along Shibamata Street in Koiwa.

・Kouwayaki Reishiyou & nicorico

・Casa Ceramica 1F, 8-20-10 Minami-Koiwa, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo