Edogawa Craft Stories

Lacquer-Black Brilliance, Forged Through Perseverance and Skill

Yamaguchi Urushi Art

Yamaguchi Atsuo

Shikkoku, literally “lacquer black,” is one way to describe the color black in Japanese—not just “pitch black,” but a rich, glossy black that looks as though it’s been freshly lacquered. Traditional lacquerware is crafted by applying sap from the urushi (lacquer) tree to wooden bowls, boxes, and other objects in many layers and features this gleaming finish. The more layers applied, the stronger the item becomes, gaining excellent water resistance, insulation, and protection from decay. Lacquerware is produced in regions all across Japan, and Edo lacquerware, with roots going back to the Edo period, is prized for its stylish, understated elegance—especially in colors like jet black and vermilion.

Yamaguchi Atsuo is the fourth-generation head of Yamaguchi Urushi Art, and today, he’s one of the few remaining specialist urushi artisans in Tokyo. His lacquerware is known for its dazzling shine—so reflective it’s been compared to a mirror. This is thanks to his masterful command of a technique known as the “roiro finishing,” which brings out urushi’s deepest luster through meticulous polishing.

Just a five-minute walk from Funabori Station, in a quiet residential area nestled between the Nakagawa and Shinkawa Rivers, is Yamaguchi’s workshop. Today, like every day, he works steadily and in silence. Many of his tools—including hake work brushes used for lacquering that are said to be 70 to 80 years old—were passed down from his father.

“This one was made by a hake brush artisan who specialized in urushi,” Yamaguchi says. “But for things like spatulas, I make my own. Most of my tools, though, are my father’s. If I didn’t have these, I never would’ve become an urushi artisan, honestly,” he adds with a laugh.

Brushes used for lacquering. Each tool, whether inherited or handmade, is treated with care and respect.

There are several steps involved in completing a lacquerware piece. The first process Yamaguchi handles is shitaji-tsuke—creating the foundation for lacquering. The surface of the wooden bowl or box is smoothed out, then raw urushi or sealant is applied and absorbed into the grain, strengthening the wood and preparing it to accept the urushi.

For box-shaped items like tiered food boxes, he first carves a slight groove at the joints between the wooden panels. Into this, he packs a mixture called kokuso: a putty of wood powder or fiber scraps and urushi. Once it’s smoothed over and set, the result is a much stronger, reinforced structure. It’s no exaggeration to say that the quality of this foundation makes a dramatic difference in the final look once the urushi is applied and polished.

Ordinarily, an urushi artisan is responsible for more than 30 different steps in the lacquering process, often working in tandem with other specialists. Yamaguchi, however, does it all himself—from start to finish.

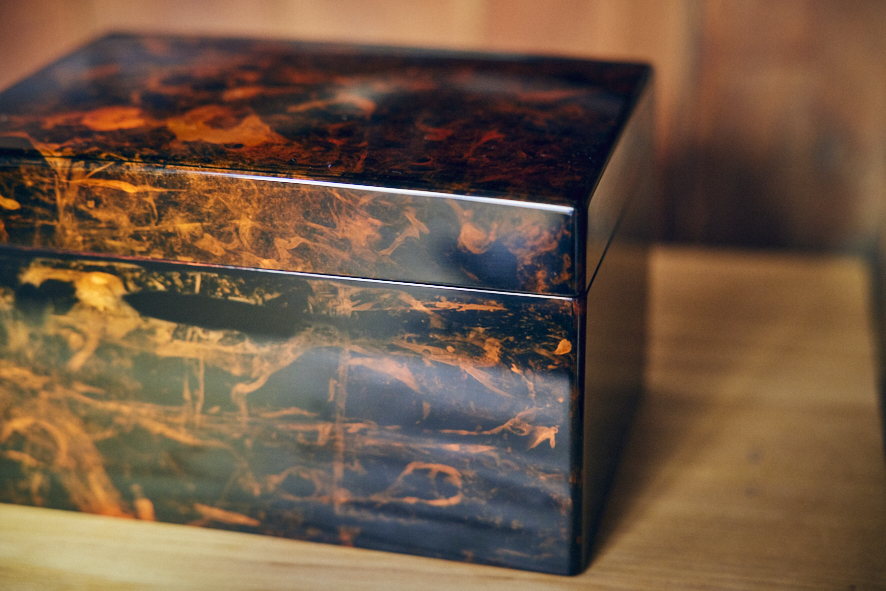

A box for tea ceremony tools, handcrafted by Yamaguchi with care from foundation to finish. The delicate balance of black and vermilion is exquisitely layered.

“I started apprenticing under my dad at 16 while still in high school,” Yamaguchi says. “The first thing he taught me was how to make spatulas, and how to mix kokuso for the foundation.”

The lacquering process includes a shitanuri (base coat), nakanuri (middle coat), and uwanuri (top coat), with each layer requiring a cycle of application, drying, and polishing to bring out that rich, glowing finish.

Especially striking is the roiro finishing technique, which creates a surface so glossy it reflects like glass—something only a seasoned artisan like Yamaguchi can achieve.

The cycle is always apply, dry, polish—again and again. “Polishing” means leveling the surface applied by hake brush—sanding down urushi layers less than 0.1 mm thick. It’s a process so delicate, it borders on superhuman. A surface that looks perfectly smooth to most people might still show the faintest brushstroke “ridges” to Yamaguchi.

Yamaguchi works on building up the urushi layers on a display stand, giving it a jet-black finish. Even before the final polishing stage, it already has a luminous shine.

“People often ask me, ‘What’s the trick to polishing?’ But it’s something I’ve learned through my body, not something I can explain in words. Everyone applies pressure differently, and we all have our own quirks. You just have to keep working until the technique becomes yours.”

Yamaguchi learned most of the over-30 urushi steps on his own, studying old documents and piecing the process together.

“My father passed away before he could teach me how to actually apply the urushi. I was 22. Up until then, I’d only done the foundation. So when he died, I was basically starting from scratch. I had to recall what I’d seen him do and figure it out from books—guessing, ‘Was it like this? Maybe like that?’ That’s how I learned to do the rest.”

It’s no surprise the path to mastering his craft was full of struggle.

“There’s no way you can just make a perfect piece right out the gate. I brought my work to a tea utensil wholesaler who’d known my father, and he’d show me pieces by other artisans and say, ‘See the difference? Once you can make something like this, I’ll pay you the same rate.’ But he was kind—he told me, ‘Until you’re there, I’ll still take your orders. Just keep at it.’ That support kept me going. I practiced through hundreds of failures. The economy was still good back then, and I had the house my dad left me, so I managed to get by.”

By the time Atsuo Yamaguchi reached his 30s, he was finally producing work that earned recognition. The wholesaler who had supported him from the beginning began introducing him to other craftspeople—urushi artisans, traditional tea utensil makers, and artisans of raden (mother-of-pearl inlay). Yamaguchi’s days were filled with sharpening his skills through collaboration with such peers. Then, quite suddenly, life shifted course: his mother fell seriously ill, and he found himself taking on the role of full-time caregiver.

“This was before Japan had implemented its long-term care insurance system,” Yamaguchi recalls. “I handled everything—from changing diapers and giving her baths to preparing meals—all while continuing my work as an urushi artisan.”

When his mother passed away at the age of 46, Yamaguchi found himself emotionally and financially drained. For the next ten years, he supported himself with a part-time job cleaning buildings while continuing his urushi work.

“I’d catch the first train of the day to get to the cleaning site, work there for about four hours, and then come home to get back to lacquering.”

Eventually, his income stabilized enough that he could give up the side job. From his late 50s, he devoted himself fully to urushi again. But hardship struck once more in his 60s when he suffered a stroke that left one side of his body slightly impaired. Fortunately, after months of rehabilitation, he regained full use of his dominant right hand and was able to return to work.

Despite the many setbacks, Yamaguchi recounts his life with calm humility. Didn’t he ever feel tempted to quit?

“There were times I felt overwhelmed. When I was younger, I used to be embarrassed about my urushi-stained fingers and would walk around with my hands stuffed in my pockets. But I never once thought about quitting. I’m the fourth generation in a family of urushi artisans—that sort of pride, or stubbornness maybe, kept me going.”

It was through his own work that Yamaguchi came to better understand his father, who had married into the family business and trained under Yamaguchi’s grandfather, eventually becoming the third-generation head.

“I heard he was struck by my grandfather during his apprenticeship. Then came the war—our house was destroyed, and the family had to evacuate. He went through a lot. When I was younger, he would scold me constantly: ‘That’s no good,’ ‘You’re terrible at this.’ But now, looking back at what he went through, my own struggles pale in comparison.”

“I’ve been lucky to have people around me who supported me. And I’ve always wanted to stay a craftsman. So now, I’m just grateful to still be at the workbench doing what I love.”

Despite enduring tremendous hardship, Yamaguchi speaks with gratitude: “I’m just thankful I can still sit here and work.”

Like the urushi that strengthens and shines with each successive layer, Yamaguchi has emerged from adversity with ever greater resilience and mastery. Even after all these years, he says that producing a perfect vermilion color remains the most difficult challenge.

“Urushi is extremely sensitive to temperature and humidity—how it dries and how the color turns out depends on those conditions. That’s why I have to adjust everything throughout the year. Vermilion is particularly tricky. If it dries too fast, it turns brownish. I try to draw out a softer shade by letting it dry very slowly.”

Layers of test applications—achieving the perfect vermilion takes countless trials, as temperature and humidity have a profound effect on the final tone.

Paradoxically, urushi dries best in humid conditions—meaning the rainy season is ideal, while winter, when the air is dry, is the most difficult. Yamaguchi maintains a special humidity-controlled room in his studio, known as the furo, where freshly lacquered pieces are left to cure without collecting dust.

“In winter, I spray down the walls of the furo to keep the humidity just right. I check vermilion lacquer work constantly. When I was in my 20s, I’d be so anxious about how the color was setting that I even slept in the studio some nights.”

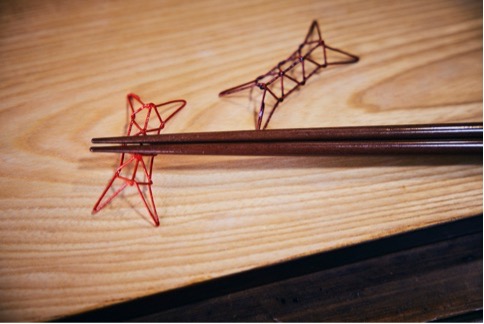

Yamaguchi primarily produces tea and flower arrangement utensils, but he’s also been enthusiastically exploring new frontiers. As part of an industry-academia-government collaboration in Edogawa City, he’s worked with art university students to create innovative lacquerware—like urushi origami earrings and chopstick rests shaped from string, inspired by the game of ayatori (cat’s cradle).

“I’m in my 70s, and they’re in their 20s. It’s a real gift to be able to connect across such a wide age gap. At first, I was surprised—‘urushi on origami?’—but when we tried it, it actually worked. Their fresh ideas are so inspiring. I hope people who aren’t familiar with urushi will come to enjoy it, even through everyday items.”

A student-inspired chopstick rest shaped like a bridge from cat’s cradle. String was formed around a custom mold and then solidified with urushi.

Writing: Makino Yoko

Photos: Honna Yuka

Introduction of the Artisan

Fourth-generation urushi (lacquerware) artist Yamaguchi Atsuo (Go Sakusuke) is one of few lacquer specialists in Tokyo. His lacquer products are renowned for their high-gloss “roiro finish,” which brings out a mirror-like shine. In recent years, he has also begun creating contemporary products such as accessories and chopsticks that cater to current tastes.

・Yamaguchi Urushi Art

・2-13-12 Funabori, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo