Edogawa Craft Stories

Updating the Dyeing Classics—Yuzen, Komatsuna, Marbling…

Kusanagi Senshoku Kobo

Kusanagi Keiko

Walk around Shinozaki Station and you’ll notice a recurring camphor tree (kusanoki) motif. Along the Toei Shinjuku Line, each station from Ichinoe to Motoyawata features a symbolic design representing the local area. For Shinozaki, it’s the camphor tree, also the official tree of Edogawa City. The floor reliefs, mosaic murals near the ticket gates, and even the clock on the station building (though no longer running since energy-saving measures after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake) all feature these puffy, tree-shaped forms. They hint at what kind of place Shinozaki is: close to nature, calm and unhurried.

Kusanagi Keiko’s studio sits a little way from the station, tucked inside a charming standalone house with a garden, in a quiet residential neighborhood. When we visited in early March, a traditional Hina doll set was on display in the entryway, a gift from her mother-in-law when her daughter was born, now over 40 years old (her mother-in-law is 105!). From the upstairs workspace, you can see the garden below—carefully tended, its spring buds just beginning to open. It’s easy to imagine how this natural, seasonal setting informs Kusanagi’s creative work.

Yuzen dyeing varies by region—Kyo yuzen (Kyoto), Kaga yuzen (present-day Ishikawa), and Edo yuzen (Tokyo). We asked Kusanagi about the differences between Kyoto and Edo yuzen.

“Kyoto yuzen reflects courtly culture, so it’s elegant and vibrant, often using bold primary colors. Edo yuzen, on the other hand, is more understated and modern; it is rooted in the lives of common folk. It tends to use more muted tones and draws from everyday motifs.”

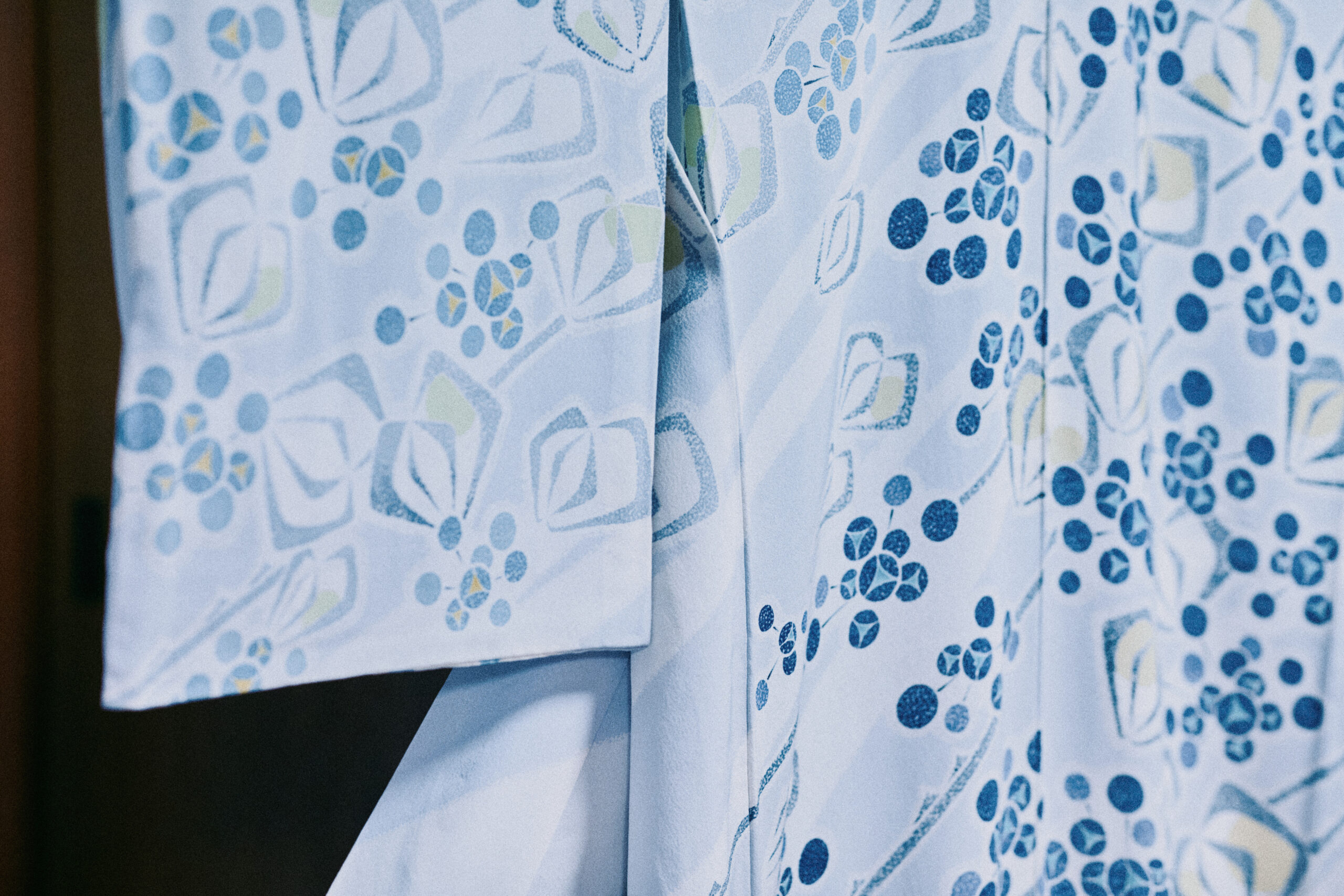

A piece inspired by sankirai (Japanese greenbrier) that once grew in Kusanagi’s garden. Though the berries are usually red, she rendered them blue for a cooler, modern effect. A major work, it took over three years to complete. (Selected for the 62nd Eastern Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition)

In her studio, a bolt of fabric in progress is stretched corner-to-corner across the room. Flipping it over reveals rows of curved tensioning needles*1 piercing the fabric—more or fewer depending on the complexity of the design. Each one is pulled tight and carefully inserted to prevent sagging. Even once the fabric is prepped, there’s still “drafting,” “resist outlining,” “base coating,” “color filling,” “masking,” “background dyeing” … each a meticulous, mentally demanding step.

In hand-painted yuzen, designs are first drawn on paper and then transferred to fabric. A fine line of resist paste is applied to the outline, preventing colors from bleeding into each other during dyeing. Since Kusanagi handles everything herself—from designing to dyeing—some pieces take up to five years to complete.

The finer the detail, the more needles required. Working without leaning on the fabric, Kusanagi gently supports each needle while ensuring the textile stays taut.

“Working alone takes time and effort, but it also means I can make adjustments as I work. And I can fully express my own creative world.”

As she spoke, Kusanagi carefully painted a light purple hue onto the petals of a bush clover using a fine brush. Before it dried, she touched in a deeper purple, blending the colors with delicate precision. Even knowing it’s all hand-painted, it’s hard not to gasp at how vividly the gradation emerges from her brush. Curious, we asked, “If the dye goes outside the lines, do you have to start over?”

“If that happens, I call in a stain-removal specialist to erase it,” she laughed. “But that takes real skill—and there are fewer and fewer of those experts around. Plus, it’s expensive. So I try to avoid it altogether!”

Yuzen dyeing is equal parts technical mastery and artistic instinct—not something you can fake with just one or the other. It’s a deeply refined craft.

Steady hands, gentle touch—but confidence is key. Kusanagi knows exactly how much dye each brush should hold, and the perfect timing to blend in a second color.

Kusanagi was born and raised in Shinozaki and has stayed there since marrying. Despite no historic connection between Edo yuzen and the area, her path to yuzen began in her final year of high school. At the time, she had hoped to become a primary school teacher but didn’t pass the university entrance exams and found herself wondering what to do next.

“I’ve always been very independent—I wanted to stand on my own two feet as soon as I could. When I was in fifth grade, I begged my parents to buy me a piano, and when the delivery truck drove through the fields of komatsuna greens carrying that upright piano, the whole neighborhood turned to watch! But I got bored and quit in my second year of junior high, using schoolwork as an excuse. I felt guilty ever since. After failing my exams, I was determined to do something with my life. My homeroom teacher suggested the Yuzen Dyeing Program at Otsuka Sueko Kimono Academy. Back then, people still wore yukata as sleepwear, and kimono were a part of everyday life. And I’d always loved drawing, so I enrolled in the three-year night program.”

Otsuka Sueko was a fashion designer who once edited the magazine Soen, known for creating postwar functional kimono styles like the monpe suit and one- and two-piece kimono. The academy was founded in 1954, and Kusanagi joined as part of its fourth cohort. At that time, sewing schools were still common, and it was normal to have clothes made by skilled local dressmakers.

At the academy, Kusanagi studied under legendary instructors, including future Living National Treasure Nakamura Katsuma. There, she learned not only technical skills but also the artistry of yuzen as a creative medium. She later advanced to the research program, where she studied natural dyes, which became foundational to her work.

After graduating, she began looking for a dye studio to apprentice at. Job advertisements for hand-painted yuzen apprentices were still common in the newspaper classifieds, and she visited several before choosing one that did wholesale work. She trained there for seven years before going independent.

“In the beginning, I didn’t get paid at all. It took seven years before I started earning, even for just a small salary. But that experience taught me something: the skills you gain can’t be taken away, and no one can buy them for you. Even while I was an apprentice, I made a point of going to see the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition every year, where my former teachers exhibited their work. The artistry was overwhelming. Unlike the commercial products I was dyeing for wholesalers, these were one-of-a-kind creations, true expressions of individuality. I admired them, but I never dreamed of showing my own work alongside theirs. I was too focused on meeting deadlines.”

But as kimono shifted from daily wear to special-occasion attire, demand from wholesalers began to decline. By the time she turned 40, orders had slowed considerably.

Motivated by the desire to make the most of her hard-earned yuzen dyeing skills, Kusanagi joined the Edogawa Traditional Art Crafts Association in 1993, encouraged by local stencil-dye artist Matsubara Fukuyo. Matsubara’s presence in Edogawa City helped forge the connection that brought Kusanagi’s work into the community.

A corner of the studio filled with tools and sketches, as well as a shelf of CDs and a cassette player. “My husband loves music,” says Kusanagi. “He introduced me to classical and jazz, which I now play while I work. It really helps me focus.”

The knowledge of plant-based dyes that Kusanagi gained in her early years would later blossom into something unique—komatsuna-dyed fabric.

Komatsuna, a leafy green vegetable, is a local specialty of Edogawa City. Kusanagi’s parents were komatsuna farmers, and she jokes that she “pretty much grew up in komatsuna.” Given that background, it made perfect sense that when taking part in the Edogawa Traditional Crafts Industry, Academia, and Public Project—a program that pairs student designers with traditional artisans—she chose komatsuna as the motif for a hand-painted yuzen necktie. These days, vegetable-themed fashion and accessories are everywhere, but in the early 2000s, designing with komatsuna was a bold and unusual choice. It perfectly captured the Edo yuzen ethos of “motifs rooted in everyday life.” The tie turned out to be a hit with people in the agriculture industry—a sign of local farmers’ deep affection for their crop.

That connection led to a new challenge. Kusanagi was approached by a komatsuna grower asking if it might be possible to use unsellable, insect-damaged leaves, which would otherwise go to waste, for dyeing.

“There’s yomogi (Japanese mugwort) dyeing, isn’t there? So, I thought komatsuna might work too. I started experimenting on my own—washing two bags full of komatsuna, separating stems from leaves, checking everything: the color, seed variety, even the tiniest details. There are many different komatsuna varieties, so I learned all about them from the farmers. The leaves gave a deep green, while the stems produced a fresher, lighter tone. I took notes on everything. Depending on the fabric, you might get a murkier color, but for things like obi-age*2, it produces a really lovely hue. Since it’s a natural dye, not synthetic, it results in a soft, gentle tone that pairs beautifully with kimono.”

Silk stoles dyed with komatsuna take on a muted young-leaf green, a gentle color that is easy to wear for all ages and genders.

This cycle of turning waste into something of value is only possible thanks to Kusanagi’s deep well of skill and knowledge. Even before “SDGs” became a buzzword, the principles behind them were already alive and well in traditional craft.

Among her most popular items are her marbled-dye (suminagashi) scarves and accessories. When you think of marbled patterns, you might picture psychedelic colors or ethnic-style fashion, but Kusanagi’s designs are refined and airy, lively but elegant. In today’s terms, they have just the right softness and clarity to flatter both warm and cool skin tones. These scarves don’t overwhelm an outfit; they blend in beautifully while adding a touch of flair.

It all clicked when someone once told her, “Marbling works well for yuzen artists, because they already understand color harmony.”

She started developing the series in the late 1990s. For a craft fair organized by the Edogawa Traditional Crafts Association, she dyed a few handkerchiefs. They sold out, becoming an instant hit. Back then, she could only manage to dye 45 cm squares. When customers began requesting scarves, she initially refused, saying “I don’t have the skills for that.” But her stubborn streak wouldn’t let it go, and she began a new round of trial and error.

“I’ve always had an interest in marbling. When I visited the souvenir shop beneath Ryogoku Kokugikan sumo stadium, they had stoles in stencil dye, shibori (tie-dye), aizome (indigo dye)… but not a single marbled piece. I kept testing, and every time I succeeded, I’d take a photo of it thinking, ‘Wow! Look how this one came out!’ The thing about marbling is you never know what you’ll get—and that unpredictability is the fun of it.”

Scarves with bold yet graceful marbled patterns. Her yuzen-trained eye for color brings a distinct refinement to the designs.

Blue tones ripple like water. These fans, each crafted by hand in Kyoto using Kusanagi’s marbled-dyed fabric, show her influence expanding into new forms.

Kusanagi has also created works that combine marbling with hand-painted yuzen—something only she could do. The idea was sparked during a 2011 Edogawa City workshop event called “Creating with Craftspeople.”

Seeking a more casual, everyday way to introduce yuzen to a wider audience, she came up with a handkerchief featuring a marbled frame with a blank space in the center. She prepped the fabric herself, outlining a seasonal motif in resist paste within the blank, and hosted a workshop where participants could apply the dyes. The event was a big hit with people of all ages, and it ended up broadening her own creative practice as well. It even led to a collaboration with the late manga artist Tezuka Osamu: she hand-painted characters like Phoenix and Princess Knight inside marbled frames.

These activities reflect her desire to pass down the beauty of kimono and traditional Japanese clothing to the next generation.

Kusanagi says she’s “easily bored,” but she’s been working steadily in the same Shinozaki room for decades. Clearly, hand-painted yuzen and the world of kimono still hold endless fascination for her. Seeing her works up close, and hearing her stories, they become even more beautiful—and even more beloved.

It’s been 50 years since yuzen captured her heart. Today, she continues to create, while also mentoring young students through the Industry, Academia, Public Project. She’s even been invited back to her alma mater for commemorative events.

In a quiet, poetic twist, the dream of becoming a “teacher” that she once held as a teenager has come true—just in a different form, through the world of yuzen.

A work-in-progress combining marbling and yuzen. A circular marbled section frames a seasonal motif, outlined in paste. The more intricate the design, the more stamina and concentration it demands.

Photos: Sakuma Akira

*1 Tensioning pins (shinshibari): tools used in araihari (washing and re-stretching of kimono fabric) to hold fabric taut during drying and dyeing.

*2 Obi-age: a narrow rectangular silk cloth used to cover the obi-makura (a padding that supports the shape of the obi kimono sash), tied above the obi to both secure it and add a decorative touch.

Introduction of the Artisan

Kusanagi Keiko, a member of the Japan Kogei Association’s Eastern Japan branch, has been involved in hand-painted Yuzen dyeing for nearly 50 years. She first exhibited at the Japan Kogei Association’s 2006 Japan Traditional Art Crafts New Art Exhibition and has since been selected five times for the Eastern Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition. Kusanagi continues to refine the traditional Yuzen dyeing technique in pursuit of her unique artistic vision, also creating practical, everyday products using the suminagashi marbling technique.

・Kusanagi Senshoku Kobo

・Edogawa-ku, Tokyo