Edogawa Craft Stories

Edo Hyogu: The Timeless Art of Framing Calligraphy and Painting

Edo Hyogu

Sasaya Yoshinori

Mounting calligraphy and paintings with cloth or paper to create hanging scrolls and handscrolls—this is the traditional craft of hyogu. With roots tracing back to the Nara and Heian periods, it is said to have arrived alongside Buddhism in the form of sutra scrolls and devotional paintings. In Edo, as merchant culture flourished, Edo hyogu gained widespread popularity. Sasaya Yoshinori, who runs a workshop in Edogawa City, began his journey into this world at the age of 16. Now 85, he remains active, continuing to refine and share the appeal of this age-old art. We spoke with Sasaya about how he got started, what makes Edo hyogu special, and the care he brings to his craft.

Hyogu involves affixing paper or cloth to calligraphy and paintings entrusted by clients, adjusting the visual composition to create finished pieces such as hanging scrolls. In Japan, the three major schools of hyogu are those of Kyoto, Edo, and Kanazawa—each reflecting the culture and history of their region, explains Edo hyogu master Sasaya Yoshinori.

“Kyoto’s style evolved with the tea ceremony—refined and elegant. Kanazawa’s reflects the dignity and richness of the Kaga domain. What I do is Edo hyogu, shaped by the vibrant town culture of old Edo. There’s a stylish playfulness that reflects the diversity of a city where people from all over Japan came together.”

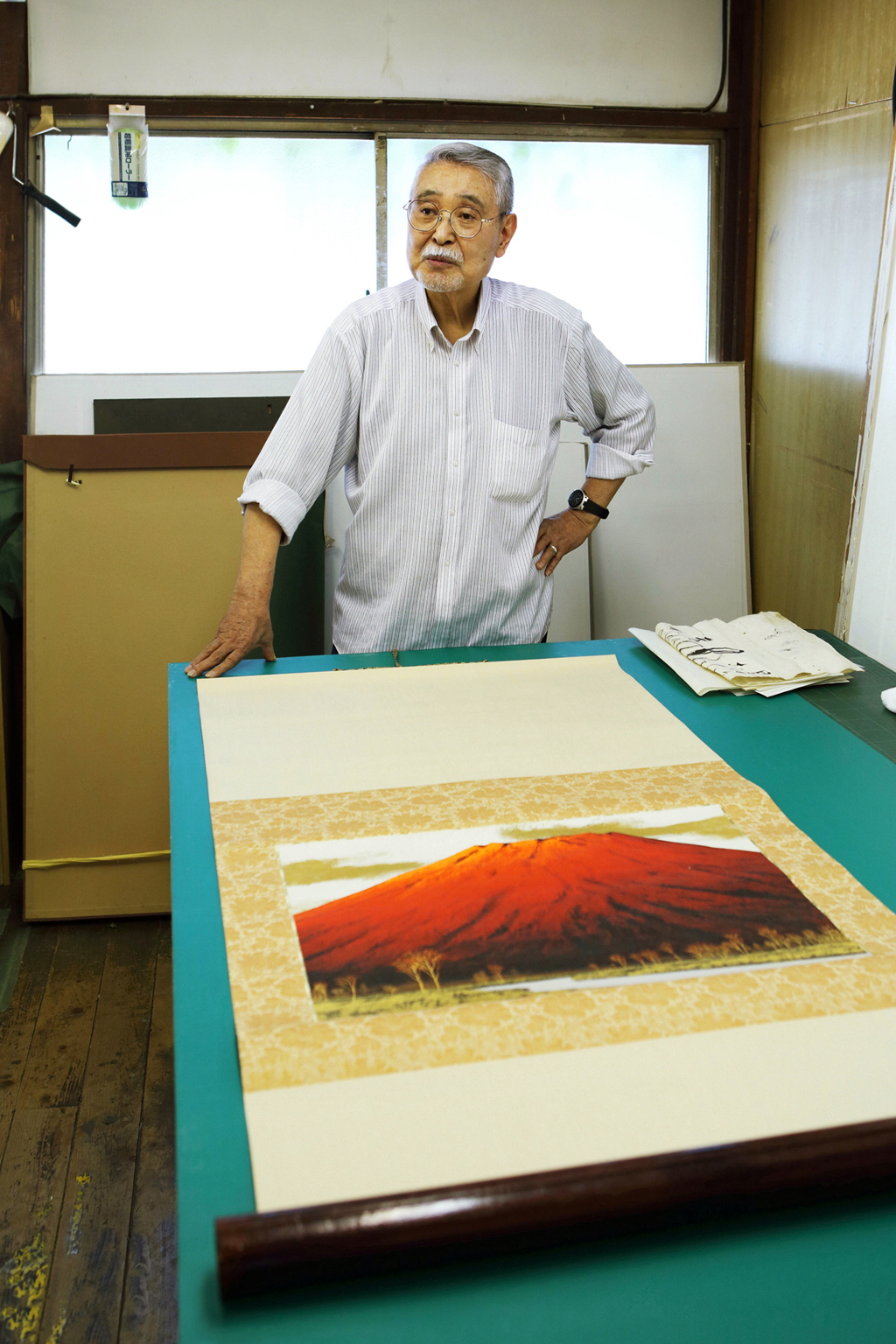

In his workshop, Sasaya unrolls a scroll of Red Fuji. The soft beige kireji (mounting fabric) draws out the vivid presence of the crimson mountain.

A Natural Talent Recognized and an Apprentice at 16

Born in 1939 in Yamagata, Sasaya lost his father early and spent his teenage years supporting his ailing mother. He had always loved drawing and was praised for his talent at school. That gift led him to Tokyo at age 16, where he became an apprentice at a picture mounting shop in Kyobashi.

“My master would first demonstrate a technique, then say, ‘Now try it yourself,’ guiding my brush from behind just once or twice. After that, it was up to me to repeat the process and learn the sequence. He’d give feedback now and then, but I also picked up a lot just by watching the senior apprentices get scolded. Our okami-san (master’s wife) was strict when it came to etiquette. Even when going on errands, she’d say, ‘The Kabukiza Theatre is nearby, you know,’ and insist I wear a dress shirt, leather shoes, and a watch. Kyobashi back then had the feel of old-town Tokyo but was also full of culture, with top musicians and art dealers coming and going.”

Sasaya reflects on his training years at his workbench. Around him are tools of the trade: various types of washi paper, hake brushes of all sizes, and other materials used in hyogu.

As his training progressed, Sasaya earned his master’s recognition. He was entrusted with the land, workshop, tools, and customer base that became the foundation of his independent practice. Now 85, he has passed the business side on to his son and devotes himself to advancing the craft of Edo hyogu.

Precision, Discipline, and 70 Years of Consummate Skill

The process of Edo hyogu varies depending on the piece. For hanging scrolls, it begins with choosing a combination of mounting fabrics (kireji) that complements both the artwork’s character and its intended display setting. Once the final form is envisioned, the piece is backed with washi or similar paper to strengthen it and shape it for mounting. The chosen fabrics are then temporarily fixed in place, and decorative elements like borders and cords are added to complete the scroll.

When working with old pieces, it’s not uncommon to encounter damage or stains. In such cases, the process begins with restoration. Since each piece is one of a kind, there’s no room for error. For instance, a torn artwork is first laid over a dampened sheet of paper and gently smoothed with a moist brush. The torn sections are then carefully rejoined with tweezers, one by one.

The torn edges of washi paper are fibrous. Watching the edge closely, Sasaya uses tweezers to gently shift and entwine the fibers back together.

“When there’s a hole, I try to blend in the repair by layering pieces of old washi whose color has aged in just the right way. That’s why I keep every scrap of washi—because you never know when it’ll come in handy.”

Once the damage is patched, a new sheet of washi is applied from the back to reinforce the piece. Sasaya moves his brush with confidence, but this step demands speed and precision as uneven glueing can lead to warping. The softened washi is stretched flat in the blink of an eye, without the slightest damage. His precision and speed are awe-inspiring.

Applying diluted glue to a sheet of washi and layering it behind the repaired artwork, Sasaya smooths it out with a soft brush. The wet washi stretches perfectly taut in moments—an impressive sight.

An Artisan’s Touch Brings Materials and Technique to Life

Choosing the right kireji is another key test of a hyogu artisan’s skill. Whether it’s matching the tone and atmosphere of the artwork or using a contrasting color to add flair, there are endless factors to consider: seasonality (like creating a cool impression for summer scenes), presence or absence of pattern, fabric sheen, and more. Without a deep understanding of material properties and color harmony, it's impossible to strike the right balance.

A hanging scroll featuring a Nihonga painting. The orange-red edge of the kireji echoes the color of the hairpin in the beauty’s hair, adding contrast and giving the scroll a poised, elegant expression.

“Even with the best materials and the most skilled hands, you can’t make good hyogu without something extra, an intuition or a spark. My master understood this well. During my training, whenever a Nihonga exhibition opened at the nearby Museum of Modern Art in Kyobashi, he’d say, ‘I’ll pay your way, go and study.’ Edo hyogu values tradition, but it also embraces flexibility and variety. He wanted us to train our eyes by seeing works from Kyoto, Kanazawa, and everywhere else.”

While traditional hyogu has long adorned alcoves and tearoom screens, Western-style homes have led to a decline in Japanese-style rooms and tokonoma alcoves. Sasaya has responded with modern hanging scrolls for walls and small items like goshuin-cho (temple stamp books) using hyogu techniques.

Items like goshuin-cho (top) and business card holders (bottom) are also made using hyogu mounting techniques—tangible ways to experience the beauty of traditional craftsmanship.

“I’m old-fashioned, so I feel a duty to preserve the skills passed down from my master. Traditional crafts are vanishing, and that’s all the more reason to keep them going. The freedom of Edo hyogu is part of its charm, so we must keep innovating.”

Passing on Skill and Sharing the Spirit of Japanese Culture

The workshop in Edogawa City, passed down from his master, is now run by Sasaya’s son, also his apprentice, who has expanded into wooden framing as well. Sasaya says he’s come to love the peaceful, green setting.

“When my master bought this land nearly 60 years ago, there was nothing here: no train lines, and a bus maybe once a day. I’d just gotten married and was used to city life in Kyobashi, so when I heard this would be our workplace, I complained that it was too far away! But now the area’s full of homes—my master really had foresight.”

Sasaya’s pursuit of the essence of craftsmanship is clear not just in his skill but in the reverence he shows toward the works he handles—and above all, in his dedication to beauty.

“Japan has a lovely word: mederu—to cherish or delight in something. People hang calligraphy, arrange seasonal flowers, and share a meal with loved ones, enjoying each other's company while surrounded by beauty. I hope we can pass on not just the technique of hyogu, but that whole way of living, a culture that values appreciation.”

Writing: Kiuchi Aki

Photos: Takeshita Akiko

Introduction of the Artisan

Born in Yamagata Prefecture in 1939,Sasaya Yoshinori began his apprenticeship under hyogu master Imanari Seiji at the age of 16, learning Edo-style mounting and the restoration of antique books and paintings. He is a member of the Edogawa City Traditional Art Crafts Association, balancing dedication to his craft with promotional work through hands-on hyogu workshops at local middle schools. In 2016, he presented an Edo-style mounting of a piece entitled Early Spring Mount Fuji to Central Coast, Edogawa’s sister city in Australia, as a gesture of friendship. Sasaya has received numerous accolades, including the Governor’s Award for Excellent Skilled Workers (Tokyo Meister Award) and the Edogawa Cultural Achievement Award.

・Edo Hyogu Kobo Sasaya

・2-1-11 Kitakasai, Edogawa-ku, Tokyo